Introduction: How to Make a Japanese Hand Plane | Kanna Plane

Since I’ve gotten into Japanese Woodworking and Carpentry, a kanna plane, or Japanese hand plane has been on my woodworking to-do list. I gave my best attempt at this thing in conjunction with the #planetrain2021 instagram challenge and while this worked to some extent, I’m chalking this up in the loss column.

With that said, don't turn away from this article. There's a lot of information I discovered along the way and at the end of the day, I did make a plane that took shavings. Just not perfect gossamer shavings. We'll get into the why of that later.

So let’s begin from the beginning. Japanese hand planes came into fashion much later than their western counterparts, with the first basic hand planes appearing around the year 1500 and versions with chip breakers on the iron not until 1900. Japanese planes are meant to be used on the pull stroke and consist of a simple low rectangular plane body also known as a dai, and a thick wedge shaped iron. Some models have chip breakers and a retaining pin, whereas others do not. I opted to go for the more primitive model, without the retaining pin.

Why hand planes? Well sheared surfaces are infinitely smoother and more refined than sanded surfaces. I actually rarely sand things anymore because of my ability to plane things smooth and the sheared, almost reflective surface is to die for. Yes, I'll spend a lot of time sharpening, but as we all know: sanding sucks. Anyway, let's get to it.

Supplies

Help support my work through the following affiliate links, all products utilized in the making of this project:

-Starbond CA Glues (Special Affiliate Link): https://bit.ly/36sB2Bv

For 10% off use coupon code: cowdogcraftworks

-The Real Milk Paint Company's Impressive line of finishing products (Special Affiliate Link): https://www.realmilkpaint.com/ref/cow...

For 10% off use coupon code: cowdogcraftworks

-Western Saws Sourced from Florip Toolworks (Non-affiliate): https://floriptoolworks.com/

The Soul of a Tree: A Woodworker's Reflections (Book): https://amzn.to/3sSEmAt

The Complete Japanese Joinery (Book): https://amzn.to/2OAj1sM

Kings County Tools Japanese Woodworking Detail Trim Saw: https://amzn.to/3baThhd

ScotchBlue Sharp Lines Multi-Surface Painter's Tape: https://amzn.to/3bchkMP

DFM Small Carpenter Square MADE IN USA with Fixed Miter Angle Pin: https://amzn.to/3u6tdwo

Center Punch: https://amzn.to/3fSQsCj

Stanley Sweetheart Chisels: https://amzn.to/2ZATrKg

Mineral Spirits: https://amzn.to/31xTBmG

Metric Japanese Style Carpenter's Square: https://amzn.to/35kC3fG

Mini Square 10x5cm: https://amzn.to/36mtcti

Faber-Castell Ecco Pigment 0.1 mm Pen: https://amzn.to/36oLni8

Pentel Mechanical Pencil: https://amzn.to/36uqbab

If you want access to more tools, check out my amazon storefront: https://www.amazon.com/shop/cowdogcra...

Step 1: The Blank

Traditionally, plane bodies in Japan are made from Kashi wood (not the cereal) or Japanese oak. This shouldn’t be confused with white or red oak, as it is a bit more closed grain, and that closed grain actually helps the shavings eject from the throat more cleanly. The wood I’ve gone with is soft maple, which is really the generic name for a number of different species that is simply not hard maple. It does not necessarily dictate the actual Janka hardness of the wood. For the most part, due to their low center of gravity, low height, and the body positioning during planing, Japanese planes tend to be more stable during planing than their narrower soled western relatives. And when making a Japanese Kanna plane, it is important to start with properly milled, flat, and square stock.

Step 2: The Layout

The layout gets confusing a bit so I’ve included the above photo in an effort to try to minimize the headaches. Basically, whatever your overall length is, you’ll divide that into a 6:4 configuration, with the dividing point being your reference line.

I went with 25 centimeters as my length, so my mark was at 15 centimeters. How did I arrive at that? 25 divided by 10 is 2.5. 2.5 x 6 is 15. I prefer using the metric system in this application because it feels a little more exact and I don’t need to fuss with fractions.

Then, depending on the type of wood you want to work with for the plane, you’ll set your bed angle or shikomi accordingly. I went with 38 degrees since I want to use this plane for more timber framing applications involving pine and cedar. However, 45 degrees would be for more standard hardwoods like maple or walnut and 52 degrees would be for extremely hard woods or exotics, acting almost like a scraper.

You also need to draw from that line a 7 degree line which will leave room for shavings to eject from the throat. Then traveling up that line 4 millimeters, you’ll use that intersection point for the opposing side of the throat, at 105 degrees. The final angle is the measurement from the top of your ejection point to the base of the plane. In this case it’s 135 degrees. However, if you’re using a higher blade angle, that number will change accordingly. Whatever your blade angle, you need to add that seven degree angle to ensure proper functioning otherwise the shavings won’t eject and jam your throat and mouth (giggidy).

Also, I've gone with a masame layout, which in this case is essentially a flat sawn layout where the rings extend upwards from the bottom. Think smiley face instead of sad face. This is to ensure that as the wood moves and changes you're always convex as opposed to concave which will make flattening the sole over time easier.

Since this is my first time making one of these, I’m using pencil and laying everything out with some various layout tools, squares and protractors. However, when I do make my next one, I’ll probably use ink as these layout lines in graphite get faint with all the handling. A little trick for more accurate layout lines is to slide your measuring tool to the point of your marking instrument, to ensure that it tracks off the pen or pencil point, instead of tracking off the side of the layout tool.

The mouth of the Kanna originates at the 6:4 reference line. Draw two lines, one at 3mm and 6mm toward the rear of the plane and use the plane iron itself to mark the overall width of the plane. You’ll be starting with the portion further towards the rear of the plane when it comes to clearing out the waste.

Step 3: Clearing Waste

Clearing out the throat is a tall task and you’re going to want to sever the grain all around before working from both sides to the reference line of the mouth. I’m going to use a jig to do the 105 degree angle, so you can stay away from that line pretty well and manage to keep things clean.

On the 38 degree side, you’ll just have to eyeball things as best as you can. These Kanna irons have a bit of a hollow where it makes contact with the bed, so you’ll not only have to chisel freehand to 38 degrees, but you’ll have to also take into account the curvature of the iron which helps keep the blade in place during use. In my case, the iron had about a 1mm curve from side to side on the back or the part that makes contact with the bed, so when marking out I took that into account.

Prior to getting started, I cut some maple to make a double sided jig. Essentially I’ve got 105 degrees on one side and 45 degrees on the other. The CA Glue and blue tape technique is an often used tactic for holding temporary jigs. Tape both surfaces, glue one, spray activator on the other, smush, and secure. Use coupon code “cowdogcraftworks” for ten percent off Starbond products here. Once the throat was pared down, I went to the side of the mouth that was yet to be cleared, the side toward the front of the plane, and secured the 45 degree jig and pared accordingly to open the mouth.

The side grooves that hold the iron are a bit tricky to clear out. I use the mini square pinned up against the mouth and aligned to the reference line for the top of the blade to strike a line. Then using a small detail saw, I saw the groove on both the top and bottom of the iron before clearing it out with a chisel and as I get closer, a file.

Step 4: Fitting the Iron

Using a pencil, I’ll color all over the Kanna iron to create essentially a graphite rubbing instrument. Then, when I’m doing the test fit, I can tap it in till it stops, pull it, then see where the graphite is rubbing off and pare accordingly. You want to do that until you actually make contact with the mouth, and then you’ll pare that open to allow the blade to pass through (this sounds a lot easier than it actually is).

A trick I have for watching the alignment of the blade is to hold it up to a light and see the light passing through the mouth. You'll be able to tell if you're high on either side and understand your fit better.

Step 5: Fit and Finish

Once the iron passes through, you want to get it adjusted laterally and get the depth adjustment right. Adjustment is pretty simple. I use a small brass mallet to give it a few taps to micro adjust it into place. If you set it too deep, just tap it the rear of the plane (the butt if you will) and the blade will back out slightly.

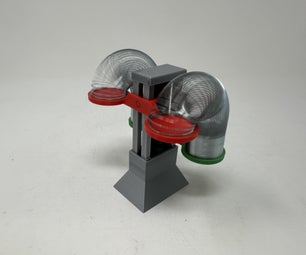

Now if you’re looking at this picture or watching the video, you should know by now that I in fact messed this plane up. I took too much material off the bed, and then made one of the channels a bit too wide, and then on top of all that discovered that the blade was cracked during the forging/smithing process and some nasty chips appeared pretty quick. Since I wanted to still try and see if this thing could pull a shaving without just throwing it in the fire pit, I went ahead and used some blue tape as a wedging/thickening device to be able to get it set. It didn’t solve the issue of the blade angle being slightly askew (the left side is a bit higher than the right), but it did allow me to pull a few shavings that were actually somewhat comparable to some well dialed western planes I’ve used. The nicks in the blade however were unavoidable. I had to heavily skew the body of the plane in order to minimize the appearance of the nicks and reduce the plane tracks they created.

So in conclusion: making a Kanna is hard. It’s not hard because it’s so complex, but really it’s hard because its deceptive simplicity requires extreme precision. Even the smallest misalignment can create issues and frankly, I’m not experienced enough in making them to be able to troubleshoot them effectively along the way. Since the iron had issues that were from the blacksmithing process, the blacksmith himself offered to take the iron back and regrind it. This actually might be a fix for me and I’m pretty encouraged to see how it goes when it comes back. Essentially, when regrinding the bevel, the overall width of the bevel, and the taper itself will change. That might cause it to fit more snugly in the side groove, but only time will tell. If not, I’ve got plenty of this maple left to try for another go.

Be sure to give the YouTube video a watch and thanks for your support!