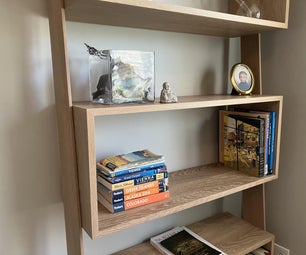

Introduction: Making an End-grain Cutting Board - I Made It at Techshop

Below are several cutting boards I have made at Techshop, San Francisco, a membership based workshop with all types of tools for making things. I don't have much experience with woodworking, so I used this project to teach myself some basic woodworking skills. I learned a lot about how to use the power-tools in the shop, how to think about wood grain, and how to glue up wood. It takes a while to make one of these, but the process is fairly simple. My first board took many hours, but later boards took 3-4 hours actual working time per piece, spread over 3 days to allow the glue to dry. I estimate the cost at about $25 - $30 per board.

Before I get started on the actual project I should thank Mark Spagnolo, whose video podcast The Wood Whisperer inspired me to do this project. Mark has a great video (Episode 7: A Cut Above) which breaks down the process well. Still, I thought I would show my step-by-step process for anyone interested, including some of the different designs I made. I also include some of the mistakes I made along the way which might trip up fellow beginners.

I am still new to both making cutting boards and woodworking in general, so if anyone has constructive criticism or suggestions, please share them in the comments.

Update: Workshop

If you are a member of Techshop in the San Francisco area, I teach a monthly workshop on making these cutting boards at Techshop SOMA. Students work on steps 1-7 in the workshop, then I demonstrate later steps with my own materials. Link to workshop pageStep 1: Tools and Materials

Tools used

- Table saw

- Compound miter saw

- Power jointer

- Power planer

- Table router

- Pipe clamps

- C-clamps OR F-clamps

- Ink-roller / Brayer (for applying glue)

- Duct tape OR packing tape

- Small scrap lumber

- Paper towels or clean rags

- Power sander and/or sandpaper

- Pencil

- Tape measurer

- Combination square

- Calipers

Materials (cost ~$25 - $30 per cutting board)

I used rough cut lumber because I have access to jointer and planer machines, and it's a lot cheaper than pre-milled (aka S4S) lumber. If you don't have access to milling tools, most hardwood suppliers will have pre-milled lumber for you to use. My local shop - MacBeath Hardwood, even has cutting board kits with pre-milled and pre-cut strips ready to glue.- Hardwood - Rough cut maple, cherry and walnut* - 1.5" thick (aka 6/4 thick)

- Wood glue - Titebond III (FDA approved for food contact)

- Finish option 1: Varnish - Emmet's Good Stuff (FDA approved food safe)

- Finish option 2: Mineral oil and natural wax (beeswax and carnuba wax are popular)

Software (Free)

- CBDesigner - A great (free!) program for designing cutting boards, discussed more later

Attachments

Step 2: Why End-grain?

Face grain and edge grain cutting boards are the easiest and cheapest to make, and for most kitchen tasks they will work just fine. But if you are a frequent cutting board user, have nice knives, or like big, heavy knives (I love my chinese cleaver!) then end grain has some advantages

- End grain plays nice with knives - Any cutting board will eventually dull your knives, but in end grain the wood fibers are arranged like a stack of straws - instead of pressing against a hard surface, the sharp knife edge slips between the fibers (second picture).

- End grain is scratch resistant - The same quality that makes these boards gentler on knives also makes them scratch resistant. After making a cut, when the knife is lifted, the wood fibers spring back into place, leaving fainter scratches compared to face grain and edge grain cutting boards.

- End grain is tough - If you select nice hard woods, like maple or walnut, and you take care of the board, your cutting board should well outlive you. Even after heavy usage and many scratches, a little sanding and refinishing will make them look good as new.

Step 3: Designing the Board

Pattern

The first three boards pictured are classic cutting board designs using stripes and checkers. they were designed using a great (free!) program called CB Designer, written by a gracious woodworker. UPDATE - Another woodworker that took my San Francisco based cutting board workshop wrote a browser-based version of CB Designer - which is also capable of managing some angled cuts to make zig-zags and chevron designs.If you play with the settings on either CB Designer, you can also create slightly more complex designs - for example in the final picture I created a staggered pattern by changing the width of just one strip of maple from 1 inch to 1/2 inch. In addition to helping you plan a pattern CB Designer helps plan what length to cut the wood, how many cuts you need to make, and how much wood will be used up in the cutting process.

If you follow the link, the creator has a video showing how to use the program.

Freestyle Design

In the last cutting board pictured, instead of using CB Designer, I used some scrap pieces of wood to make something more creative than normal stripes or checkers. CB Designer can't handle this type of pattern, but it's easy to think up your own design. I took some scraps of bevel-cut wood from other projects and thought about different ways I could arrange the pieces into interesting patterns. The possibilities are endless, I have seen other's create diamond patterns, flowers, and waves - just remember to think about your design from the perspective of end grain. I sketched out my ideas on google docs, brainstorming 4 different possible patterns using the end-grain profile of my scrap pieces.Even though CB designer can't show these freestyle patterns, you can still use it to calculate the length of your wood pieces and the amount of wood waste.

Lumber choice

Cutting boards can be made out of any wood, though some woods are better than others. The important thing is that it is a hardwood, with dense fibers, small pores, and no toxic oil / sap / chemicals. Hard maple (aka rock maple) is the classic choice - other common woods include cherry, walnut, purple heart, and yellow-heart.Many other woods will work, but it's a good idea to do some research before choosing exotic woods, which may not be food safe. Some woods contain a lot of natural oils, which can be toxic or cause problems for people with allergies. Other woods, while food-safe, may not be the best choice because of their grain structure - soft-woods and open-pore woods such as oak or ash may allow more liquid to soak into their fibers, giving bacteria a place to grow.

If using rough-cut lumber, like me, make sure to look at the condition of the wood. Cutting boards are constantly exposed to liquid and moisture - rough cut wood that is already warping at the lumberyard may be much more prone to warping in your kitchen - look for straight boards.

Also, pay more attention to the end-grain pattern of the lumber instead of the face grain pattern. Knots or figure that may look interesting on the face of a board will not be visible in the finished board, because only the end grain will be showing. Knots or heavy wood figure may even be hiding empty spaces in the center of the board that will show up as a hole in your cutting board once you cross-cut and expose the end-grain.

Thickness

Anything from 1-2 inches is common for a cutting board. Make it even thicker to create an old-school butcher block or whole end-grain countertop. In general thicker boards will be more stable while cutting, are less prone to warping from moisture, and can take more re-finishings after heavy use.Remember that the thickness of your cutting board is not directly determined by the thickness of your lumber. When making an end-grain cutting board you get to determine the thickness of your board based on the cuts you make (step 9). The thickness of the lumber just determines the width of the individual strips on your board.

It's important to determine the thickness of your board before you cut any wood. When making my first board I used CB Designer to make a 1.5" thick board, but at the last minute changed my mind and made a 2" thick board - this 1/2 inch difference had a big effect when multiplied by 11 cuts. The end result was still nice, but much shorter than originally planned (First example pictured).

Step 4: Cut the Wood to Length

Cutting with the miter saw

- Check the length of your kept piece. Once you are satisfied with the length, place / clamp a stop-block at the edge to measure all other pieces to the same length. If using a shared saw like at Techshop, double check that the miter angle is set to 90 degrees, and the bevel angle is set to 0 degrees.

- Place your hand on the kept-side of the wood, pressing it against the rear fence and the stop block. This supports the kept piece and makes a clean cut. Do not hold the off-cut side of the wood, which can lead to messy cuts and kickback by trapping the kept piece between the blade and stop block.

- Fully extend the saw blade and turn it on, wait for it to come to full speed before lowering it into the wood, push forward through the cut.

- When finished, wait until the blade stops before lifting the saw. Lifting while the blade is still spinning can create a messy edge

Step 5: Jointing and Planing

The end result this step can vary widely based on the quality of the wood used. My boards were fairly straight and flat from the lumberyard, so I did not have to remove a lot of wood to square the edges, but the faces were quite rough with some small cracks.

To joint the boards

- Check the condition of the wood - place it on a clean, flat surface and see if the faces are cupped or twisted. Choose the flattest side and place it face-down on the jointer, with the grain facing forward toward the cutter.

- Feed the board through the jointer, taking thin cuts (less than 1/16"). Keep your hands away from the blades at all times - using grip pads like those pictured not only keeps you safe, it ensures even, consistent pressure throughout the cut.

- Repeat as necessary until the board is flat and smooth. Only one face needs to be jointed, the other face will be cleaned with the planer.

- Check the edges of the wood, see if the board is bowed right or left. Again, choose the flattest edge and place it down on the planer bed.

- Feed the board edge through the jointer, making the same thin cuts. Repeat until one face is straight and smooth. The opposite edge should be cleaned up on the table saw - unless both edges are already perfectly parallel, jointing both edges will only compound existing imperfections.

To square the edges

- Check if the edges of the board are parallel, using a combination square. My maple was nearly perfect, while my cherry and oak were both tapered.

- Place the jointed edge of the board against the table saw fence, with the narrowest end facing toward the blade. Fit the narrow end of the board between the blade and fence, then lock the fence in place

- Push the board through the table saw, shaving off the unjointed edge of the board. You should now have a square board.

Plane to thickness

- Check the un-jointed face of the board. If it is cupped or bowed, you will need to take multiple, shallow passes through the planer. Measure the thickness of the board and set the planer depth of cut to the same thickness, or just below it. Set the depth for shallow passes (1/16" or less) to ensure a clean cut.

- Place the jointed face down against the planer bed, with the grain facing forward towards the cutter.

- Feed the board into the planer. Let the power-rollers pull the board through the cut - don't get your fingers anywhere near the entrance of the planer.

- Use the same depth setting to plane all boards that will be used at the same time, to ensure consistency

- Repeat until you reach the desired thickness (the top "thickness setting in CB Designer) or until both faces of the boards are flat and square, and all boards of of equal thickness.

Step 6: Rip Strips

To rip strips

- Set the fence the desired width away from the edge of the blade, so that the strip being cut runs between the blade and fence.

- Place the board down on the saw bed (Optional: use a feather-board for extra support - place the feather board IN FRONT OF the saw blade, not next to the blade.

- Feed the board through the saw blade. For added safety, especially when working with narrow strips, use a push-stick to push the end of the board past the saw blade. Repeat until all strips are cut.

Step 7: First Glue Up

Tools:

- Titebond III - Waterproof, FDA approved for food contact, and has a longer drying time than other glues, which give more time to fit pieces together and make adjustments.

- Ink roller - Bought from a local art store, an ink roller is better than a brush for this job because it spreads glue quickly and evenly, leaving more time to assemble the pieces before the glue starts to dry.

- 2-3 Pipe clamps or parallel clamps - Other clamps may work, but pipe clamps are good because they apply even pressure and they lift the piece up off the work table.

- 2-3 'cauls' - Pieces of scrap wood that can be clamped vertically against the glue-up to prevent them from buckling under the pressure from the pipe clamps. The cauls should be just shorter than the total width of the cutting board.

- Duct tape, packing tape or wax - Coat the cauls with tape or wax, both of which are glue-proof and stop the cauls from sticking to the wood.

- 4-6 F-style or C-style clamps - These clamps hold the cauls vertically against the work.

- Damp rags - Used for wiping away runaway glue and keeping the roller damp after use. Alternatively, after use the roller can be put in a bucket of water.

- Putty knife - for scraping away squeezed out glue

To glue up strips:

- Lay out all of the strips, edge down, and double check they are in the correct pattern. If using CB Designer, this is the first image labeled "Edge-grain Cutting Board."

- Once you are sure everything is correct, turn each piece over, face-down, except the first piece and push them all together.

- Squeeze glue out over the face-down pieces, then use the roller to spread the glue evenly across all the pieces. (steps 2-3 pictured)

- Set the roller aside, wrapped in a damp rag or bucket of water.

- Take the un-glued piece and place it into two pipe clamps. Now do the same with the first glued piece, pressing it against the first piece. Repeat until all the pieces are inside the clamp jaws.

- Slowly close the clamp jaws into the pieces. Don't apply full pressure, just use enough pressure to hold the pieces in place. Use the cauls to align the ends of the strips and hold them even (step 6, pictured).

- Place the cauls on top of the cutting board, just above the pipe clamps. Use the F-clamps or C-clamps to hold hold down the cauls. Put the top jaw of the clamp onto the caul and the bottom jaw under the pipe clamp.

- Now apply full pressure to the pipe clamps. The pieces may want to twist out of alignment or buckle under the clamping pressure - nudge them back into place while the glue is still wet (steps 8-9, pictured).

- Optional: If working with long pieces, you may want to use a third pipe clamp laid on top of the cutting board to ensure even pressure across the whole length of the board.

Take a break

Wait 1-3 hours, then unclamp the board and use a putty knife to scrape away the squeezed out beads of glue. It's a lot easier to clean the glue now instead of later, while the glue is dry but not fully hardened.

Step 8: Clean Up and Planing

Check the board

If everything went perfectly, then the ends of the board should be even, there should be minimal glue residue and the edges of the board should be flush and unbuckled. If this is the case, then give the board a light sanding to clean up any glue and move onto the next step. But more often than not, something will go slightly wrong - here's how to solve common problemsFixing problems

Problem 1 - Ends uneven

If one of both ends of the board have misaligned pieces, they need to be trimmed. I used the compound miter saw to trim my board, but you can also use a table saw and crosscut sled or handheld saw.Problem 2 - Light glue residue

If the edges of your board are properly aligned, and the only surface problem is glue residue, then the face of the board can be sanded smooth. Make sure to get ALL the glue, it's very important to have smooth faces for the next two steps.Problem 3 - Buckled pieces or heavy glue residue

If the strips of your board buckled up or down; if you forgot to scrape the glue off the board; or if there are other major surface defects - then sanding will take far too long. You should probably use a scraping tool, such as a hand plane or spoke shave, or just put the whole board through the power planer - which is what I usually do.Step 9: Exposing the End Grain

But, to take the board to the next level, you need to cross-cut the board into strips to expose the end grain. If using CB Designer, the width of your cross-cut piece will be the final thickness of your END grain cutting board, seen at the bottom of the program

To crosscut my strips, I prefer to use the table saw and crosscut sled, which gives me clean, square cuts. (Update) If you don't have a crosscut sled, I would really suggest making one - one afternoon of work making one will make your future table saw experience safer and much more accurate. However, it's also possible to make the cut by carefully using a miter gauge to push through the cut. User Kieth726 described a safe method, see his comment below.

To cut on the table saw

- If you have one, put a crosscut blade on the saw - this will give very smooth sides to the cut. Next, setup a cross-cut sled using a stop block set away from the blade the width of the cut you need to make. Make a test cut on scrap wood if necessary.

- Gently place the board against the stop block, then firmly hold the board DOWN against the sled. Push the sled through the saw. Repeat until the end. Check width as you go - all pieces should be the same width, if there is any variation stop and fix your setup - any variation between the pieces is fixable, but it can be a major pain after glue-up.

- The final strip may be too small to cut safely with the crosscut sled. Either find a hands-free way to hold down the final piece, or remove the sled and cut the final piece using the fence and a push stick. Measure the distance between the fence and blade using one of the already cut pieces. See second picture for extra-safe alternative.

- Some of my pieces got burned by the table saw - cherry is especially easy to burn. Don't worry too much about this, the burn marks will come out later when sanding the finished cutting board.

Cutting on the miter saw

- The miter saw makes quick and clean cuts and is a good alternative to a table saw. However I have an important safety note for anyone considering this route. (See the final picture)

- Since the piece being cut is so small, there is no easy way to hold it steady while making the cut - if using a stop block this can create a dangerous situation where the cut piece get trapped between the blade and stop block. In my case this caused one of my cuts to explode into several pieces which flew around the room. Luckily none of them hit me or anyone else.

- This can be avoided by using a pencil mark or soft stop block to measure the cut pieces, or making some kind of jig to hold the small pieces steady as they are cut.

Step 10: Second Glue Up

Also, be extra careful to avoid SMEARING wet glue over the surface of the board. Normal squeeze out is fine, but end grain is the thirstiest part of the wood, and loves to soak up glue, which may lead to discolored spots later on.

Glue-up process

- Lay out all the strips in front of you with the end grain facing up. If necessary for your design flip pieces to arrange them. This is also a good time to play around with the end grain patterns to see if there are any interesting ways to arrange the pieces. See the second picture below for an example.

- Set one piece to the side, end grain still up, then turn over all the other pieces on their sides. Press all the turned pieces together and get ready to glue them. Make sure your glue, roller and clamps are all ready to go.

- Squeeze glue across all the turned pieces, then use the roller to spread out the glue evenly. If there are any bare spots add a little more glue - these joints need to be completely covered with glue.

- Put the first unglued piece inside the clamps, then add the first glued piece and press it against the piece in the clamps. Add all the pieces until the board is complete. Set the ink roller aside in a bucket of water or damp rag.

- Gently close the jaws on the pipe clamps, not to full pressure, just enough to hold the pieces in place.

- Use the taped cauls to align the edges, then put the cauls on the board above the pipe clamps. Use C-clamps or F-clamps with the top jaws on the cauls and bottom jaws on the pipe clamps.

- Now add more pressure to the pipe clamps, watching the pieces for any shifting or buckling. If you are making a complex pattern, make sure all the lines and contrasting color wood still line up correctly, unclamp and make changes if necessary.

- Once all the clamps are tight, and the board looks flat and square, take a break

Come back 1-2 hours later, unclamp the board and scrape off the squeezed out glue. Try to get as much as you can - end grain can be very difficult to sand so a little work now will pay off big later. After scraping, I suggest leaving the board to dry overnight again.

Step 11: Flattening the Cutting Board

(Update) Hand plane + fine sanding

After playing around with Techshop SF's brand new set of (sharpened) hand planes, I am now convinced that a good hand plane is the best tool for the job. I've only tried hand planing one cutting board so far, so I'm still improving my technique, but it got the job done MUCH faster and better than my old belt sander + hand sanding method. Instead of taking 1 hour + to sand the board, it took about 10 minutes. And whereas the electric sanders leave scratches or swirls that must be further sanded away, the plane left very few tool marks - and with more practice maybe no tool marks.The board I hand planed is perfectly flat, but needs a little sanding with fine grit sandpaper to further smooth it. But maybe that just means I haven't found the perfect style of plane yet. From what I've read in the comments and on several other websites, a low-angle block plane or low-angle jack plane are best for end-grain planing. So far I've only used a standard angle plane, and though the result was good, the operation was a bit choppy at times - I can see how lowering the angle might make a difference.

I don't have any pictures or instructions, since I'm still learning how to use this tool myself, but I will update my instructable as I learn more.

(Update) Belt sander + hand sanding

This is the method I used on my early cutting boards, but it's now my secondary method. It produces good results, but takes over an hour to finish a single board. If you are just making one or two cutting boards, and don't have access to a hand plane or other electric surfacing tools - then this method will work fine. But if you are making multiple cutting boards, like me, then please save yourself the hassle and get access to a quality hand plane or a drum sander.- Start with the belt sander - This machine can take a lot of material fairly quickly. Don't try to get the board completely smooth, just sand down the largest glue spots and uneven strips.

- Once the board is mostly flat, switch to a random orbit sander or palm sander. I started with 80-grit paper, then moved onto 150 grit paper.

- In the next step I will be adding handles and a juice groove using a router - final sanding can wait until after the router cuts.

- If you are happy with the board like it is now, then soften the sharp edges with the 150 grit sandpaper or a block plane, then give the whole board a final sanding with 180 or 220 grit sandpaper. Make sure to sand the sharp edges smooth.

Drum sander

This is the perfect tool for this job - if you or anyone you know has access to a drum sander, then use it. A drum sander is setup just like a planer, but instead of blades, it uses sand paper to 'plane' an item. Sadly I do not have access to a drum sander, and commercial models can be quite expensive, so I had to use other methods. I have heard cabinet shops and professional woodworkers can be convinced to help out for a small fee. I've also found many DIY versions online for a fraction of the retail price.Power planer

Possible, BUT RISKY. Power planers are generally not designed for cutting END GRAIN - If something goes wrong, both the cutting board and the planer knives can end up getting damaged. See this article from The Wood Whisperer for more information and examples of problems. Not something I'm willing to try with Techshop equipment, proceed with caution if you try this.Please note, the above warning is only for END GRAIN cutting boards. If you decided to stop early, after step 7, and keep your EDGE GRAIN cutting board, then the power planer is a perfect method for flattening your project - go ahead and use it.

Router sled (or CNC machine)

One final method that I have read about, but not yet tried is using a router or CNC machine to flatten the surface of the cutting board, then hand sanding to finish. Here is an example, courtesy of LumberJocks.com. Also here is an episode of The Wood Whisperer using the same router method. I'm interested in the idea - not just for flattening my cutting boards, but also for flattening boards that can't fit into the jointer / planer machine. If I ever try this method I will update my instructable with the results.Step 12: Shaping the Edges

To make your board even more functional you can cut out handles, a juice groove, and round-over the sharp edges. I prefer to use a table router for these cuts, but a handheld router or even a CNC machine would be good alternatives. In addition to routed handles, on some of my boards I decided to use kitchen cabinet handles attached to the cutting board with epoxy.

There is a video of my process at the end of this step.

EDIT JAN 2015: The table router method shown for the juice groove works, but it's hard to get aligned correctly. If you have access to one, a CNC is the easiest way by far to cut a juice groove. For those without access to a CNC machine, a hand router with edge guide as shown in my referenced podcast from The Wood Whisperer is another great way to get it done. If you proceed with a router table based juice groove, make sure to perfect your technique and settings on scrap wood BEFORE carving your beautiful cutting board.

Before you start cutting the final piece, it's very important to make sure you have selected the right router bit and set it up correctly - I strongly suggest making test cuts on a piece of scrap wood before cutting the actual project

Handles on a table router

- Set up the table router with a rabbeting bit or straight bit and a fence centered over the bit. If using a rabbeting bit, the guide bearing will decide the depth of cut. If using a straight bit, decide the desired depth of your handles and set the fence that distance behind the router bit.

- Place a strip of tape on the fence above the router bit .Take a piece of wood and touch it against the left and right side of the bit - make a mark on the tape where the edge of the wood meets the bit. Marking the tape like this will let you see where you are cutting even when the bit itself is covered by wood. For extra guidance you can set up stop blocks at the beginning and end of the cut, like in my picture.

- Now take your cutting board and decide where you want to cut the handles. Take a pencil and mark the left and right edges of the handles on top of the cutting board.

- Turn the router on, place the cutting board in front of the router and line up the left mark on your cutting board with the left mark on the tape above the router bit.

- Push the cutting board into the router bit until it contacts the fence. Then move the cutting board to the left until the right mark on the cutting board meets the right mark on the tape above the router bit. Pull the cutting board away, you should have a perfectly routed handle.

- Repeat with other sides as necessary.

Juice groove on the router table

- Change the router bit to a box core bit

- Routing the juice groove follows the same process as the handles, except that the cut begins in the center of the wood.

- Again, mark the left and right sides of the router bit on the fence above the bit.

- Again, mark the edges of the juice groove on the board (or use stop blocks). I wanted mine at 1/2 inch inside the top face, so I marked 1/2 inch away from each corner. Use stop blocks for extra guidance, if desired.

- Set the router fence 1/2 inch away from the back of the router bit (or however far in you want the juice groove), and do some test cuts on scrap wood to decide how deep you want the groove to be.

- Turn on the router, and line up the left mark on your cutting board with the left mark on the tabe above the router bit.

- Carefully lower the cutting board onto the router bit, keep control of the board, don't let the router bit move around.

- Quickly move the project left until the right marks on both the cutting board and tape align. Lift up the cutting board.

- Repeat as necessary to all sides.

The first time I did this, I burned my wood quite badly at the beginning and end of the cuts, but it got easier with practice. It's important to stay in control of the cut at all times, but the quicker you make the cut the less burning occurs. Another good reason to practice with scrap wood. To clean up the burn marks I used a sharp chisel to pare away the darkest parts, then hand sanded the groove smooth.

Round the edges

- For the top edges I used a 1/4 inch round-over bit with a guide bearing, running all four edges along the bearing edge

- For the bottom edges I used a 1/8 inch round-over bit with a guide bearing, running all edges along the bearing edge. To reach the inside edges of the routed handles I used sandpaper to make the 1/8 inch round-over.

Video

Table router alternative

To cut handles or a juice groove using a handheld router, use a straight bit with an edge guide to cut the handles, and the same box core bit with a pattern made from scrap wood. I have included a still-capture from The Wood Whisperer video of Mark cutting handles using an edge guide.

Yet another option would be using a CNC machine. In addition to cutting perfectly sized handles and grooves, you could cut ornate shapes and other embellishments.

Step 13: Finishing and Future Care

To apply mineral oil (and wax)

- Give the surface a final sanding with fine sandpaper - 220 grit or higher. Then thoroughly clean away all sanding dust.

- Flood the surface of the board with food grade mineral oil - pour it on and spread it around evenly with a rag.

- The first coat of oil should quickly soak into the board. If you make a thin board some may even come out the other side. Let it sit for a few minutes then wipe away the extra oil.

- Leave the board to rest overnight, then repeat the flooding process. Do this until the board stops absorbing oil.

- (Optional): After applying 1-2 coats of pure mineral oil, you can further waterproof the board by adding wax to the oil. You can make your own oil/wax mixture or use commercial premixed products such as Howards Butcher Block Conditioner, which I used.

- To make your own oil/wax finish heat up a mixture of 75% mineral oil and 25% wax over low heat or using a double boiler. Microwaves do not work very well on wax.

- Apply the oil/wax mixture the same as the pure mineral oil, flooding the surface of the board then letting it rest for a day. Repeat until you are satisfied with the wax finish on the board.

- When the board will no longer take any oil or wax, buff it clean with a clean rag. You are done!

To apply varnish

- Give the surface a final sanding with fine sandpaper - 220 grit or higher. Then thoroughly clean away all sanding dust

- Use a mixture of 50% food safe varnish (aka salad bowl finish) and 50% mineral spirits (NOT mineral oil)

- Wipe the varnish/spirit mixture onto the cutting board with a rag. Keep applying the varnish until the cutting board stops soaking it up. If you turn the board over, some may even come out the other side of the wood.

- Let the board rest 8 hours or more, then re-apply the varnish, using long even strokes

- Let the board rest another 8 hours or more, give it a light sanding with 400 grit sandpaper (or grade 0000 steel wool) then apply a final coat, again using long even strokes

- Let the varnish cure, give it a final fine sanding, then wash off any dust. Your cutting board is finished!

- It's important to remember, unlike varnishing a piece of furniture, you don't want to build up a layer of varnish on top of the cutting board. That's why the varnish is thinned with mineral spirits, so it soaks deep into the wood and avoids forming a film.

Future care

- To care for a cutting board finished with mineral oil, it's recommended to re-oil the board once a month under normal use. Wash the board with soap and water, but don't let it sit in a wet sink or put it in the dishwasher.

- It's not necessary to regularly condition a varnished cutting board, but when knife marks start to show on the cutting board surface you can seal them with a coat of mineral oil - only use as needed. Wash with soap and water, but don't let it sit in a wet sink or put it in the dishwasher.

The controversy

- Which material is safer to eat from?

- Which material keeps the wood more sanitary

Mineral oil

Varnish

Step 14: Updates

Related instructables

Participated in the

Hurricane Lasers Contest