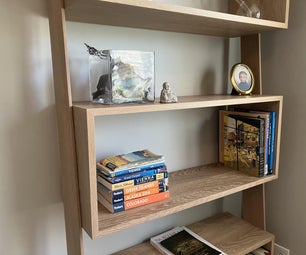

Introduction: Heirloom Tool Cabinet

Over the years I've amassed a collection of traditional woodworking tools. When I was in town I always visited the Jamestown flea market vendor and found very nice locally sourced tools from the NC furniture industry, but that vendor has been gone for 10-15 years at this point. Some of these tools I bought new myself, or received as gifts. Some came from my grandfather and great uncle. One from my father-in-law. Some were gifted heirlooms that belonged to my friend Gordy's grandfather and great-grandfather. Given the personal connection, I felt somewhat obligated to keep them safely stored and accessible for use.

If you have ever seen the Studley tool chest, you know where my design inspiration came from. Virtuoso: The Tool Cabinet and Workbench of Henry O. Studley (Donald Williams, 2015) has detailed photos by Narayan Nayar that show the details of Studley's epic piece. Studying that design in my copy of the book, I realized I just don't have the patience to create miniature columns and keystone arches to keep a hand plane from falling out of the holder. I pretty much picked some design elements I could easily replicate and tried to keep this from taking a thousand hours to finish. One thing that makes Sudley's chest look so cool is the multiple layers of tools. When you look at his chest, you see front-row tools with some tools lurking in the dark behind the front row, and another layer behind that. I managed to get some layers, but not the same density or detail as my inspiration. Being in the piano business, Studley made extensive use of ebony and ivory. This uses ebony and mother-of-pearl and abalone inlays, but I went with my own style for the graphic layout. Another Studley design idea is keeping most of the chisel handles the same dark color. So I picked a few ideas and then went with my favorite materials.

The focus of this write-up is on the design process. If you have a collection of vintage tools, I'll assume you already know how to build a plywood box and drill holes to hold a chisel. Given that, I try to spend time describing the strategy for design choices, and show some of the unique details of my construction techniques. Another assumption is that the statistical probability of someone having the identical set of tools is nearly zero. So there isn't a measured drawing of how I fit all these tools together. But I do show how to come up with the dimensions that will work with your tools. Outside dimensions are 25-1/2" x 42" for the main cabinet, the door is 4" wide, the hinged hand plane rack is 22" long and hinged 8" from the back. These dimensions will get you room for large planes and handsaws behind them. Other than that I don't get much into measurements. But it should be pretty obvious how big things are given the tools for scale.

Supplies

Safety First: 3M Ammonia Methylamine Respiratory Protection Cartridge 6004, AOL Safety face shield, 3M safety glasses, 3M ear plugs, push sticks, vinyl gloves, nitrile gloves

Layout: 9mm Graphgear soft lead mechanical pencil (I love these pencils), marking knives, rosewood marking gauge, Starrett combination square 150mm/5-3/4" 10MEH-150 (recommended highly), Sharpie, Bates combination square, Steadler compass, Starrett dividers, tape measure

Adhesives: Arrow high-strength glue sticks, Titebond PVA glue, Duco Cement on the threaded wood

Saws: Porter Cable cordless recip saw, Bosch jigsaw, Dewalt miter saw, Craftsman 10" table saw, HF bandsaw, Stanley backsaw

Planes and Chisels: what is shown in the tool chest

Router: Ridgid trim router

Stationary Shop Tools: Grizzly dual drum sander, Ridgid 8" jointer, Craftsman drill press, Jet dust collector, Cricut Maker 3 vinyl cutter

Wood: MDF core white oak plywood, 4/4 white oak, 1/4 resawn white oak from a local supplier, rough cut gaboon ebony from ExoticWoodZone on eBay

Inlay: mother of pearl and abalone inlay from jnnpearlinlay on eBay, veneer sheets from an eBay assortment, .svg cut files on Thingiverse

Hardware: commercial ball bearing hinges, spring loaded case handle, metal box hasp lock - all Amazon

Pneumatic: Porter Cable brad nailer and stapler

Cordless: besides the recip saw, Porter Cable impact driver, Porter Cable drill

Chemicals: Ammonium Hydroxide 28%, Novacan black patina for zinc

Finish: Zinsner shellac, Deft clear wood finish semi-gloss

Step 1: Plane Rack

A couple of constraints influenced the size of my cabinet. First off, white oak plywood is really expensive so I wanted the interior to be exactly half of my 4'x4' sheet wide at 24". Then, using the golden ratio of 1.618:1 I set the interior height around 40" for good proportions. With these rough dimensions I laid my tools on a table to decide how to arrange them. And I don't mean I spent five minutes getting it looking good, I took over an hour trying different layouts then slept on it and came back the next day for adjustments.

This project uses 1/4" resawn white oak heavily. It came from a local hardwood supplier, and is absolutely indispensable for this project. With the resawn wood in hand the planes are laid out, using 1/4 scraps as spacers. I used the resawn oak to support the bottom edge of the plane, but would have been better off using the thicker 4/4 stock.

Is this all lovingly dovetailed and mortised like fine furniture? Heck no. I use hot-melt to hold the boards in position, use a center finder bit to countersink, pre-drill for the root diameter of the #4 wood screws, and fasten with the screws. The hot-melt works like cushioning gasket, and removes easily with a squirt and soak in 70% isopropyl alcohol. Most of the intricate pieces in this project were tacked with hot-melt and screwed or tacked in place. Other steps tack pieces with the grain perpendicular, which will almost definitely rip apart with seasonal wood movement. The hot-melt will pull loose, and the countersink hole is slightly oversized to allow for movement. But if it does fail, it designed to be disassembled and reconfigured as necessary.

To get the layers of tools, the plane rack is screwed onto a plywood backing. I traced the voids in the rack onto the plywood and cut away under the planes to give a layered appearance. I suppose the entire plane rack could have been built as a single piece from hardwood, but using 1/4 white oak plywood as a backing support balances a good look with project completion time.

Step 2: Brass Tabs

I fabricate optical positioners for osteological specimens, so I have a pretty good supply of brass around. For rotating tabs to hold tools in place, I use brass tabs. If you haven't ever tried to machine brass with wood tools, it isn't as hard as a hitting a dried out old pine knot. Plus a piece of wood this small is going to be annoyingly prone to splitting. Using a 5/16" x 1/8" brass bar one end is rounded on a coarse belt sander, then at the center of the rounded radius it is center punched and countersunk. Cut to length on a bandsaw and cleanup on a sander until you like the looks. I like to go in and chamfer the edges on the sander, but watch your fingers.

Step 3: Inlay

Pick some good places to add inlay. Is there a big void between the legs of a divider? Drop some inlay in to fill the space. Does something sort of 'point' at something else? Make it point at inlay.

The black background photos show using a 1/2" Forestner bit to make a recess for the inlay dot. This gets filled with hot-melt and used to mount the inlay. Hide glue would work, and a beauticians body wax melting pot makes a handy glue pot, but that stuff is a mess to work with. I know hot-melt is pretty weak, but it is nearly impossible to get an intact dot out of the hole if it goes in too deep so it doesn't take much to keep it held in place. It takes some experience to get how to put just a little too much glue in the hole, then press it flush with a board and chisel the squeeze out. But after ten or so, it gets easy.

The large round inlay was cut on a Cricut Maker3 vinyl cutter. These are nice machines with not-so-nice proprietary software. I included a link to the design in the supplies section. The .SVG vectors are color coded to cut the diamonds first, then the circles. Import the .SVG into DesignSpace, tape down veneer on the mat, and set the cut for about any heavy material that you have a Cricut knife for. I used heavy cardstock settings. You could likely hand cut this pretty easy with a scalpel taped to a divider leg, or trace inside a piece of pipe. But I had a new toy and wanted to play with it. It is installed with hot-melt, and sanded flush. Careful sanding, if it gets hot it will re-melt the glue and things start moving around.

Step 4: Inlay Stringing

The gaboon ebony makes a mess of black powdery dust in your shop. The only thing I've ever worked worse than this was graphite I machined to make push molds for boro glass working.

The rough ebony material is too thin to go in the drum sander, so I tacked a sled together to get some additional thickness. Start with enough material to finish your project and keep sanding until it is smooth, then take it down to the width of your bit (1/4" usually). With the wood thicknessed, cut stringer inlay strips on the bandsaw. My process was to cut, then hand plane the remaining work piece flat, and cut again so each piece has three good sides. The bandsawn side goes into the routed slot on the edge of the white oak. Go about 1/2" thick for the edge banding, and a little less than 1/4" deep for the routed slot. For the plywood edging, route the slot first then nail into the slot and cover the nail with the ebony. The case for the door is solid white oak so there are no nails to contend with.

Something that definitely doesn't work for cutting a recess for the round inlay is to leave a little stub of ebony sticking into the hole, then trying to cut it flush with a Forestner bit. The ebony splits and looks like tooth brush bristles. Either cut exactly to length, or use a chisel to make the recess round again.

Step 5: Brass Saw Holders

The design for the saw holder is pretty basic. Since saw handles are made from 4/4 wood, you can use the 4/4 white oak to make dividers. Cut to length and screw in place from the back side and bottom of the cabinet shelf. But the way saws are balanced relative to the width of the cabinet, the saws are prone to falling back into your face. Ask me how I figured this out.

To hold the saws in place I make barrel shaped connectors from 5/8" brass round stock. Cross drill with a #12 drill bit to get a slip fit for 3/16" rods, then center drill and tap for 10-24. Thread the 3/16" round stock to fit in one end of the barrel, and use knurled 10-24 thumb screws to lock in place. The white oak will hold 10-24 threads, but a coating of Duco cement before screwing the brass into the wood will soak in and harden it nicely. This is the same adhesive they called model airplane dope way back before my time.

Step 6: Fuming

Do not think you can just hold your breath and escape the fumes that come off high strength ammonia. Trust me, I tried. The fumes will burn your hands as you pour it out, what it does to your eyes, lungs, and sinuses is ugly. Full face respirator with ammonia vapor cartridges, or stain it with Minwax.

But after that harsh warning, fumed white oak is the coolest finish on the planet. You get all sorts of wood figure popping out, and the color just can't be matched. The general idea is to build a tent around your project, pour some ammonia in a bowl, and come back to stained wood in a week. For a tent frame, I used some fence pickets and 2x4s I had around with blocking to support the corners. A painters plastic dropcloth worked, but I've had better luck with thicker plastic. I think the thin sheet moves in the wind and pumps fresh air into what should be a nicely toxic chamber. But it works.

Interestingly the ammonia turned the purpleheart a ghastly grey color, but then some shellac and lacquer and it was purpler than ever.

There are multiple shots showing before and after photos.

Step 7: Finish

This is my favorite combination of finish for wood projects. The shellac is very thin with solvent, and soaks down into the wood. It dries fast so it is easy to apply a couple of coats. But just use enough shellac to bring out the depth, the lacquer is what builds the layer on top. The end result is a smooth finish on top that has a very good depth to show the figure of the wood. Both of these materials dry very fast, don't require sanding between coats, and can be re-coated without sanding.

Step 8: Drawers

Again with more fine woodworking sins. Perpendicular grain, hot-melt glue, and wood screws. Everything is just butted together, these just won't get the kind of use that requires better construction. I've dovetailed plenty of drawers, but for something I might only open every few years devetails are overkill. Rather than attaching a strip to the side I just made the bottom wider and cut a matching slot to slide in the cabinet. There are screw holes in the ebony handle behind the pearl inlay.

Step 9: Interior Details

Here is a random collection of interior shots. You can see how the saws just rest on the shelf edge For the hinged chisel holders, having a set if 1/64" incrementing drill bits that goes up to 1" is really helpful to find a snug fit. Where a chisel tip is wider than the ferrule, a slot was added. For the marking knife holder, it is a drilled hole opened up with a bandsaw. The cabinet is held together with wood screws that are mostly covered up or treated with a black patina.

Step 10: Hinged Panel

The hinged panel uses a 1/4" brass pin threaded into a 3/4" ball. The balls are available from lamp making supply houses. A screw would likely work fine as an alternative, I just had the material around to do it like this.

Step 11: Exterior Trim and Hardware

With mostly everything finished, it is time for the trim. I did cut the hinge mortises before finishing. There are all kinds of online how-tos for mortising hinges. My twist is to hot-melt the hinge, center drill for the screws, partially install screws, with the hinge held in place use a marking knife to scribe the borders of what will be routed, then hand route the mortise and clean the corners with a chisel. For the hinge screws, some black patina will make galvie screws turn black. Spraypaint or a Sharpie will also work if you don't want to special order patina for color matching screw heads. You can find the aluminum angle and corner protectors by searching on 'road case supplies'. The aluminum cuts with woodworking tools. I spray painted the aluminum black since the interior details are black ebony.

Step 12: Making a Hook

Here is a detail of how to make a hanger hook. There are multiple variations of the hook in this project. Drill the bottom to the width of the hook mouth, then bandsaw up to the hole. Watch those fingers in case the wood splits in the bandsaw while you are pushing it into the blade.

Step 13: Interior Pieces

Here are the removable pieces for the interior, shown fully finished. The last shot shows a focus target I printed that helps with creating good photos.

Step 14: More Photos

I'll leave you with this unedited collection of photos. You can see how different camera settings impact the overall mood of the photos. And if you are more into the tools than the cabinet, you can see them up close. Anyway, enjoy the photos. I like to talk, so feel free to ask questions in the comments and I will make every effort to respond.

Thanks for checking this out.

Second Prize in the

Woodworking Contest