Introduction: Drilling Metal

This is the third lesson in my online Metalworking Class and it is focused on drilling metal. Chances are that you are probably already familiar with the concept of drilling. It simply involves putting a round hole in something using a spinning tool. The most common tool used in metalworking is a drill press. However, since you are just getting started and don't know whether or not you yet like metalworking, I am not going to ask you to invest in one. Instead, for now, we'll just be using a corded drill to make our holes. This will get the job done for what we are doing, but just not be quite as precise (as you will see).

(Note that some of the links on this page are affiliate links. This does not change the cost of the item for you. I reinvest whatever proceeds I receive into making new projects.)

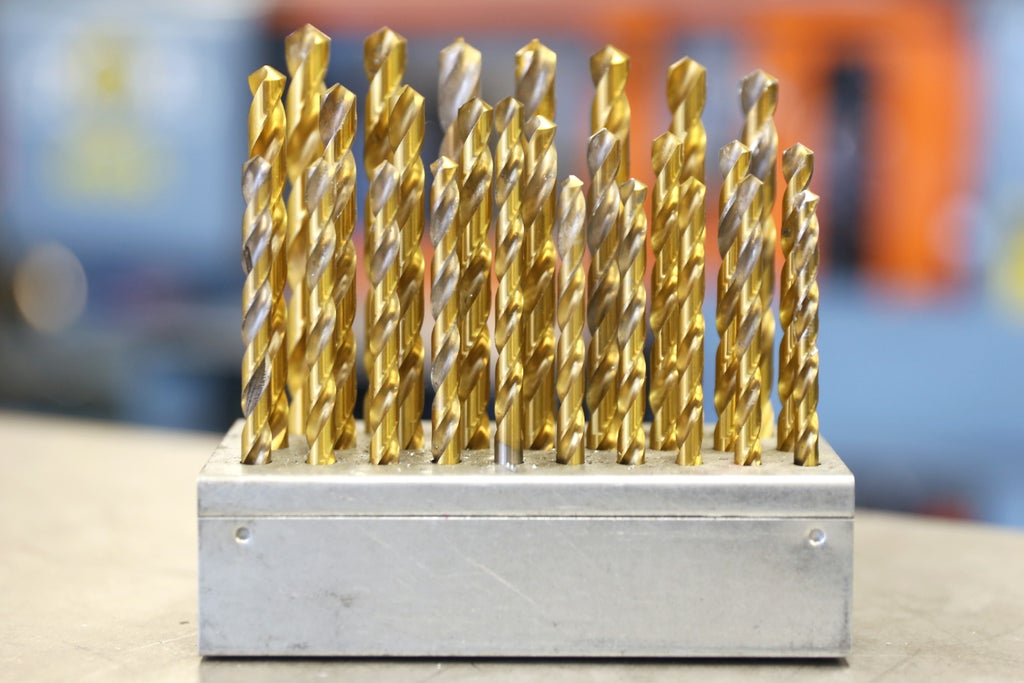

Step 1: Drill Bits

The primary type of drill bit you will use when metalworking is a split point drill bit. These bits have two cutting surfaces or blades, which are angled together to a point in the center. They are also angled in such a way that it cuts away material as the drill spins clockwise. The cut material is then cleared away through the spiraled flutes (channels).

The opposite end of the drill bit is called the shank. It has no channels or blades, and typically has been hardened to withstand the forces of cutting. Typically, the shank will have a marking which indicates the diameter hole the drill bit cuts, and the type of steel it is.

Since we are working with aluminum, standard multipurpose carbon drill bits should do you just fine. However, when working with harder metals like hardened steel or stainless steel, you will want to use something manufactured to cut hardened metal such as high speed steel drill bits. You can see the HSS marking on the pictured drill bit shank which indicates that this one is in fact high speed steel.

Step 2: Sizing

Split point drill bits tend to come in different sizes, and to confuse matters, there are three different sizing systems you may encounter. These include metric drill bits, fractional (imperial) drill bits, and gauge drill bits.

The gauge drill bits use a number and letter system starting with 80 (the smallest), and going up to 1 (the largest). This is subsequently preceded by a letter system starting at A (the smallest), and going up to Z (the largest).

In the chart above you can see all of the different drill bit sizes from the three systems listed by size, and all converted to inches. A poster like this is a useful one to invest in for your shop if you ever get into serious machining.

Step 3: Specialty Drill Bits

There are also all kinds of specialty drill bits you may use while metalworking. Some of the most common you may use include hole saws which make large holes, spade bits which make larger diameter holes than average split point bits (in softer metals like aluminum), and countersink bits.

As you move deeper into the world of metalworking, you will learn there are many kinds of drill bits to choose from.

Step 4: The Drill Press

A drill press is a stationary shop tool with a spinning chuck that spins a drill bit really quite fast. Even though that is the basic gist of it, there is actually much more to it than that. Even though we will be using a hand drill I will be remiss if didn't briefly go over the functions of a drill press.

Like a motorized saw, drill presses have their own required speeds and feeds.

The speed is typically set before you begin drilling by setting the proper configuration of pulleys or gears. Is is determined by the diameter of the drill bit, and the hardness of the metal being drilled. The goal is to cut as much material

as possible without creating too much heat.

The feed is determined by the person using the machine. By turning a crank or lever on the side of the machine, the machine operator can determine just how fast to try to move the drill bit through the part. While this is dead simple to operate, it can take a lifetime to really master.

Step 5: Now You Try!

Now is time to drill some holes to call our own. We will be drilling three holes into the end of our teleidoscope tube that we will be threading in the next lesson. These ultimately will be used to hold the teleidoscope lens in place. By the end of this process, you should have a fairly reasonable understanding of what it takes to drill a hole in a piece of metal.

Step 6: Get the Right Drill Bit

Since we are making holes to be threaded, it is very important that we make the hole precisely the right size. If it's too big or too small, we won't be able to cut threads into the side of the hole. Since we are using 6-32 bolts (more on this in the next lesson), we will need a #36 drill bit.

Step 7: Measure and Mark

However, before we can go at and drill the hole, we need to make sure we get our measurements correct. As they say, 'measure twice, cut once.' In other words, make sure your measurements are correct before you do anything.

Draw a marking 0.2" parallel to the edge of the aluminum tube.

A trick for doing this is to use a set of calipers. Dial the jaws in to your measurement, and use the set screw to lock it in place. Use one jaw to follow the edge of the tube, and the other to trace a marking around the circumference.

Step 8: Measure and Mark Again

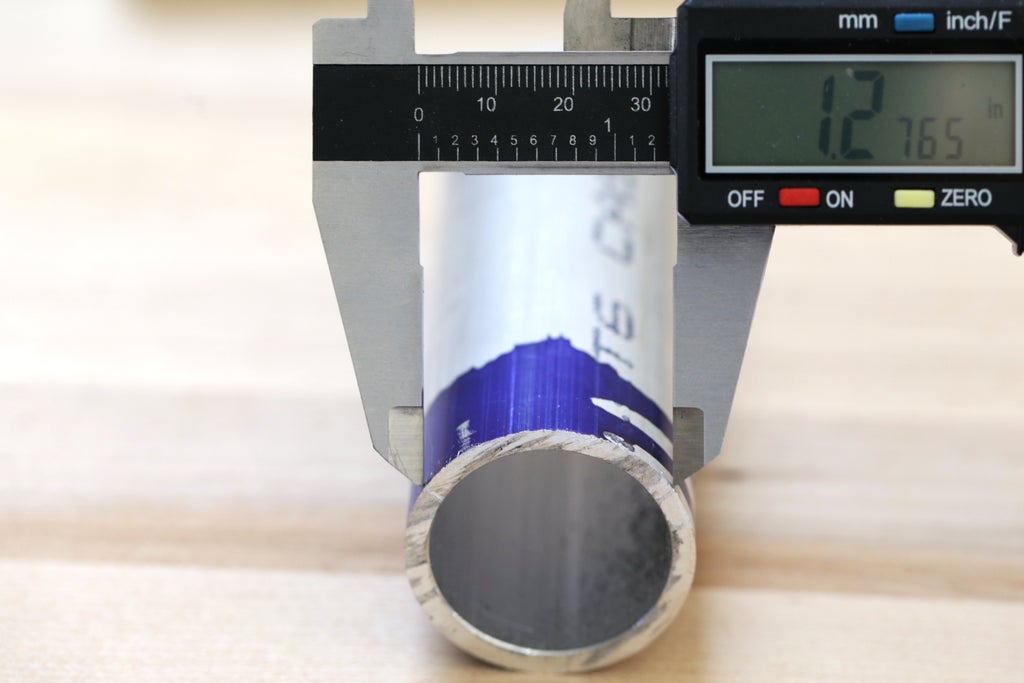

Next, you want to use a scriber to draw perpendicular crosshairs along the circumference line that you have just measured at three equally spaced points around the circumference of tube. Figuring out three equidistant points along the surface of a round tube is very difficult. I would not judge you if you eyeballed this to get it right, as the precise spacing is not entirely important for these holes.

However, should you want to be precise, you can use your calipers to measure out an equilateral triangle along the round surface of the tube, and then drops lines down to intersect with the circumference line. The points should be approximately 1.275" apart.

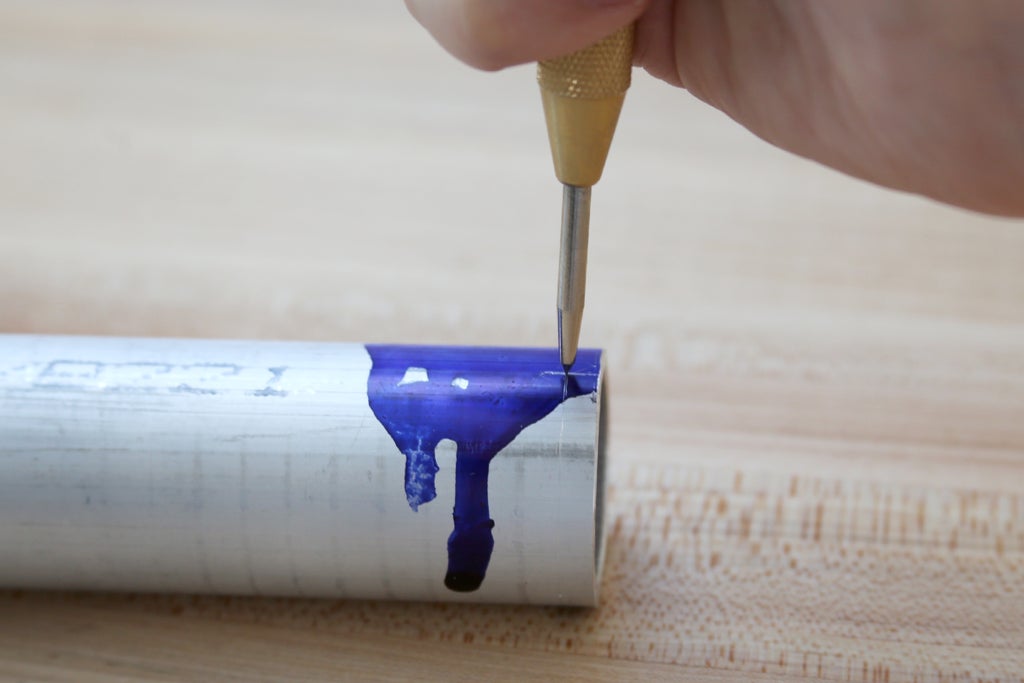

Step 9: Center Punch

Now is time to punch a dimple into the three crosshairs that you just marked. This will give the drill bit a starting groove to spin in, and prevent it from wandering off-center. If you drill without first doing this, your drill bit will wander all over the piece of metal.

To make this indent, place your part on a nice firm surface and go grab a punch. This can be either a spring-loaded punch, or a more traditional center punch.

To use the spring-loaded punch, place the tip of the punch on the center point and push down until it forcibly kicks back at you. This is quick and easy.

A traditional center punch can leave a better marking, but it is a little bit trickier to use as you have to align the punch with one hand and give it a swift hammer tap with the other. As you will notice, doing this to a round surface (that has a tendency to roll) can get a little tricky.

Step 10: Clamp

After punching three dimples, clamp the aluminum tube in the vise with one of the center punched dimples face-up and centered.

Notice that the area I am about to drill is clamped firmly in the jaws of the vise, as opposed to hanging a bit off the edge. This is to ensure it stays firmly in place while it is being drilled.

Step 11: Position the Drill

To begin, insert the shank of the drill bit into the chuck and tighten it firmly in place.

Place the drill bit centered in the dimple left behind by the center punch.

Step 12: Begin Drilling!

Next, it's time to begin drilling.

When you are drilling, if you are seeing lots of small flakes, you are going through the material with the right speed and pressure (feed). This will take some trial and error to get right.

Step 13: Drilling Pointers

If you are seeing long stringy bits of metal spiraling out of the hole while drilling aluminum, it means that you are applying too much downward pressure and/or your drill bit is spinning at the wrong speed.

These stringy bits can get wound around the drill bit and start to spin around. This is not good because they can be sharp, and possibly spin out and cut you, or damage your work piece (more likely with steel than aluminum). Thus, this should be avoided.

To stop this from happening, back the drill bit out slightly to break off the chip (metal strand). Then, adjust the speed or amount of pressure being applied until you start getting nice small chips.

A common technique used for getting nice small chips is to use peck drilling, which means that you move the drill bit down a little bit, back off to let the metal clear, and then repeat. This is done until you are all the way through.

Step 14: Close Enough...

As you will find, even with a center punch, manually getting the tip of the drill bit perfectly on center is very difficult with a hand drill. It will likely be off slightly (especially when just getting started). Don't worry about this. This is okay for the project that we are making.

However, this is ultimately why hand drills are less preferable than a drill press for metalworking. A drill press allows you to perfectly position your part and clamp it into place.

Step 15: Clean the Edges

Drilled holes, like cut edges, leave behind burrs. Typically, these can be easily filed away.

Since our burrs are on the inside of a round surface, we will want to use a round file to remove them. You don't need to get too zealous here, just file enough to remove them. If you can run your finger over the hole and the surface feels mostly flat and smooth, it's good enough.

Step 16: Repeat the Process

Drill and deburr the remaining holes if you have not done so already.

Once you have completed this, you are now ready to move onto the Fasteners Lesson.

Did you find this useful, fun, or entertaining?

Follow @madeineuphoria to see my latest projects.