Introduction: Freaky Gargoyle Chair Built From All-reclaimed Wood and Leather

This is my gargoyle chair. I love it. It is easily my favourite build for years. It lives in my workshop and I regularly just sit in it and laugh because it is so freaking satisfyingly weird :)

Why?

I made this it because I like weird stuff and it's kind of cool to chill out seated on your own creepy beastly throne. Everyone wants that, right? I love this chair so much.

Made from thrown away, scavenged and abandoned stuff

The best thing is that it was made entirely from discarded, scrapped and waste materials The main chair structure is made entirely from reclaimed oak, by rough jointing heavy baulks of wood together then carving it into the gargoyle figure you see. It's very solid.

The very comfortable padded leather upholstery is based on the shape of a crocodile's belly and all the leather and internal padding came from a thrown away sofa.

The total project budget was a very modest of about £20 ($25) for a few bits and pieces from my shed like a few screws and glue and I did buy French polish. The rest was scavenged and reclaimed form trashed and discarded stuff.

I like this sort of extreme recycling. I am always amazed at the quality of raw materials that are thrown away. Here's what you can do with it if you keep an eye out for good stuff in the rubbish.

What is covered here, that you might find useful

If, like me, you like weird, creepy or any other generally absurd stuff and you want to build something similar in wood, there's probably some technique in here that will be worth considering. I've tried to include as much depth of detail as possible for each method used so you should be able to recreate it or build upon it. Some steps are about simpler techniques than others, but none are especially difficult. This was a lengthy build. It required patience more than anything.

I've split the different processes into self-contained steps as far as possible, so if you only want to figure out one technique, you can see it all in one place. Roughly speaking these things are covered:

How to get excellent quality raw materials for free, from stuff people throw away...

- where to find quality scrap wood that can be salvaged and reclaimed for free

- how to disassemble a sofa to reclaim materials such as leather, foam, fluffy filler and wadding

How to work out the practical construction plan for a complex irregular design

- conceptualising and working up a structural design for a carved form

- sketching in 2D using drawing and 3D using rough DIY physical prototyping

Practically building a complex chair frame using standard and non-standard jointing methods

- heavy mortice and tenon joinery to create a base structure from which to carve the final shape

- connecting complicated shapes using custom pin and glue joint

- how to join up multiple blocks and layers of wood when making irregular forms

How to adapt carving techniques to tackle complicated forms in wood

- roughing out with hand rasps, power saws, power planers and sanders

- traditional hand-carving using chisels and gouges

- power carving using rotary rasp in the hand-held router and Dremel

Rough upholstery on a complex frame

- building up decorative panelling for the chair back and seat

- using old carpet off-cuts for strengthening the inside of the upholstery

- stuffing with recycled polyester fibre

- fitting irregular stuffed edge piping

- reinforcing the seat base with plywood and screws

Finishing techniques

- traditional home-made iron and vinegar wood staining for antiquing oak

- filling using wood plugs, and glue-and-sawdust paste

- progressive sanding passes from power sanders and to fine finishing using steel wool

- French Polishing

Step 1: Scavenged Materials

Quality materials reclaimed from stuff thrown away

I like to make things out of old stuff that has been thrown away.

In making this chair, all the wood for the frame and all the leather and padding for its upholstery came from reclaimed, recycled or foraged materials. In fact, pretty much all the raw materials used to make it were "waste" material that had been chucked away by someone:

- Old oak fence posts collected from hedges and skips over the years

- Oak fascia boards scavenged from the skip outside a decorative fireplace shop

- Green oak logs left behind after trimming back a storm-damaged tree

- Leather from an unwanted sofa that was on its way to the dump

- Foam rubber block from the same scrap sofa

- Fluffy stuffing material also from this sofa

- Sprung steel from an old thrown-away saw blade

- Stainless steel sheet from a skip

- Various offcuts of plywood, also from skips

- Some offcut sections of a carpet I kept when we had it fitted a few years ago

It is very satisfying making things using the really good-quality materials that are frequently thrown out as rubbish. I did used some shop-bought glue, a few nails, screws, sandpaper, steel wool, wood glue, hot glue, rivets and French polish, to pull it all together but that was all. Everything else was from scrap.

Here's what was used in this Instructible and where it came from

It's mainly about the wood

The most important material in the chair is oak wood. All the oak was recycled from discarded and/or unwanted wood. It took quite a lot of getting together.

Reclaimed waste oak from various sources...

You can see examples of most of the various wood used in this build in this picture. Left to right they are

- Reclaimed partially sawn green oak log (with mould discolouration) - the arm-rests were carved from this

- Reclaimed raw split green oak log - the claw ends for arm-rests were carved from this

- Vintage weathered oak fence post - the chair legs, arm uprights and chair frame were made by joining sections of this

- Carved reclaimed green oak log - this is what the log in example 2 looked like when carved

- Another section of partially-sawn reclaimed green oak log - also carved into an arm-rest

- Reclaimed oak floor board or wall panel offcut - the carved skeletal back was made by gluing together jigsaw cut layers of this into a boat shape then carving it.

Old fence posts

The original gargoyle stool was made from nice solid oak from old fence posts that came off a property that had been built in the 1930s. It is quite possible that they could have been originally in place at that time. If so they could be as old as 80 years old, which is kind of cool.

Even if not quite that old, they are almost certainly at least 50 years old. The oak would have been green wood when the posts were made. By the time I got hold of them they were lovely solid baulks and a pleasure to work.

Oak is very hard and goes a lovely orange colour. Here you can see a post in its raw form as it was found. It is being fitted to extend the carved gargoyle to add an arm-rest support. Although it may not look like it, the carved creature is made from exactly the same wood as the post.

Oak plank offcuts

The chair back was built from oak floorboard off-cuts. I couldn't believe my luck when I found these thrown away in a skip about 10 years earlier. I had these in the shed ever since, waiting for a decent project. The convex curve of the back was built up from several pieces glued together and further shaped, before final carving of the vertebrae details.

Raw wood from logs

But most satisfyingly, the armrests and the claws on the end of them were carved from green oak which I cut from foraged logs. These were logs left behind by the foresters when they had finished felling a large oak that had fallen in a storm. I was carving from this wood about a year after it was cut, so it was not fully seasoned.

This is a block of oak cut from a log

To get this, I cleaved it from a log using axes. For control, the axe was not being swung. It was used as a wedge and hammered into the wood using the heavy lump hammer. Oak splits quite easily, despite being so hard.

Here is a raw log and a claw made from it...

This log was distorted because it was from the shoulder of a branch of the original tree. It was used to make arm-rests. You can see saw marks. These are from a circular saw. This was the only saw I had to hand.

Luxury upholstery materials on the cheap

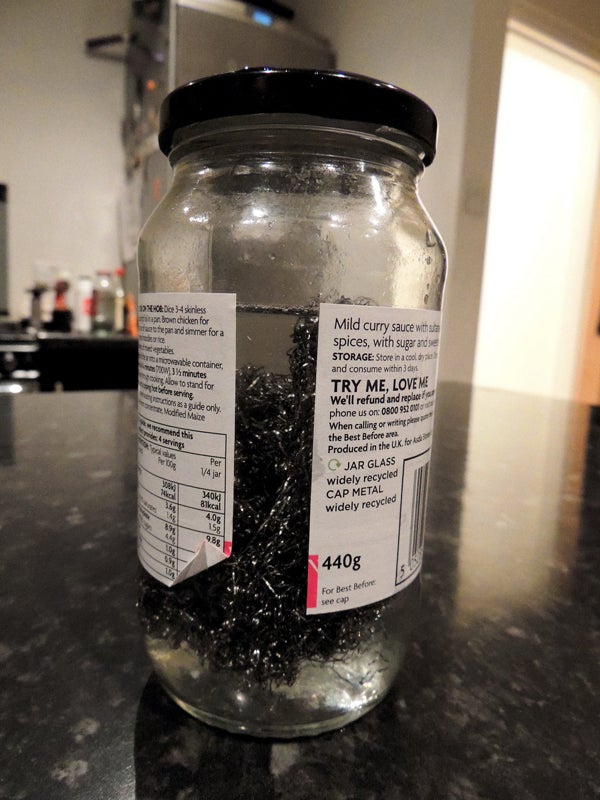

The other main source of materials was this unwanted sofa, which was offered free on gumtree or its owner would take it to the dump. Look at all that lovely leather!

This was dismantled...

To get metres and metres of leather...

This was carefully trimmed off with my penknife.

It would have been a shame to have thrown this into landfill. It is top quality leather.

It's easy to remove because the thread used to sew leather is usually pretty coarse and widely spaced so, you can pop the stitches with no real effort.

As well as big pieces, you get a load of handy smaller bits. On the left you can also see the foam rubber that I got from the sofa.

And here is some fluffy polyester filling material. Very springy and versatile for irregular shaped upholstery.

Here it is out of the bag

The sofa had loads of foam rubber cushioning...

Other construction materials

Defunct saw

This old discarded handsaw - this was not being used as a tool. The whippy steel was recycled and used as to create the internal spring mechanism for the spring-loaded back.

Reclaimed stainless steel sheet.

Found thrown out in a skip. Used to make a counter spring in the chair back

Reclaimed offcuts of plywood from skips, used in the lower chair back

Glue, stain and finishing materials

Wood glue for mortice and tenon joints used to join fence posts to construct the chair frame and legs before they were carved

Waste plastic bottle

This is a glue spreading spatula cut from a mosquito repellent spray bottle

Sawdust - by-product of sawing and rasp-carving

Sawdust and wood glue paste was used as filler. Although often considered a waste product, saw dust has very good filler properties as it is rough and fibrous and adds bulk and strength.

Oak blackening stain

This is a stain made from diluted vinegar and steel wool. This creates a dark liquid that reacts with tannin in oak to stain it black. Used to age oak.

Step 2: Designing Creepiness That You Can Sit On

This project was a labour of love. I like grotesque stuff and I just wanted to make something that you wouldn't forget it in a hurry when you saw it.

As well as making it look creepy and slightly disturbing, I also made it to feel good to the touch. Its smooth forms feel strangely warm and bone-like. Sitting on it and running your hands over it is a pleasure.

But if nothing else, it was rather good making something unique just because I felt like it.

Inspiration

Here are some of the sorts of things I like. The chair is not an attempt to recreate any of them. It just riffs off the general grotesque beauty of this sort of thing. Later in this step, you can see how I sketched out ideas to turn abstract ideas into something that you can actually sit on as a functioning piece of furniture.

I like any weird stuff, so things like this are good:

Classical gargoyles - this one is from Barcelona

They don't have to be beasts...

...and weird heads of any style. These are all from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The skeletal back of the chair is one of my favourite things about this chair. Skeletons are fascinating. I love them. The chair back had no fixed design. It just had to feel "vertebral".

I carved it freehand with a general idea in mind. It riffs off various inspirations like Giger's mutant vibes in his Alien designs. I also think I must have had Jan Svanmajer's short film Ossuary lurking about in the mind too, which showcases thousands of plague victim remains in the Sedlec Ossuary.

Jan Svankmajer's classic stop motion film "Ossuary"

Built then rebuilt

The chair was originally something I made in about 1997 from old oak fence posts. The chair was originally a stool. In 2016 I significantly remodelled it to give it arms and a back. Now it is much more grandiose and throne-like.

I don't have any photos of the original stool being made. However, the exact same jointing and carving techniques used to make the original stool were also employed to remodel it into this much more exotic version.

Original version (1997) and final version (2016)

I loved the original, but I had to admit it just wasn't that comfy to sit on. After nearly twenty years, I decided to give it a back and arms to make it comfy. The challenge here was to do this while keeping the grotesque charms of the original. To do this meant a load of sketching and later prototyping of chair backs...

Sketching out designs...

For me, drawing is the best way to get an idea to formulate in the mind

It is worth investing in a load of decent quality pencils. Even good ones are pretty cheap. I keep a full range from super soft (9B) to super hard (9H) and everything in between. The most common softness I use is a 2B. You can sketch light or dark lines with different pressure, and you can smudge it with your finger and soften it back with a rubber to work up a design sketch quickly.

Rubbers are tools too!

Do not be afraid of using a rubber (aka an eraser). When in the flow of a drawing, I find I am more creative if I can rub out bits that aren't quite right and just keep scribbling to rework it without pausing.

Copying to gain familiarity

Copying is an underrated technique for working up a design.

As the 2016 build involved a redesign, I started by copying the original version of the chair, to see how I could develop the design while keeping it in the spirit of the original.

Original chair frame with upholstery removed to see the structure

This is an initial familiarisation drawing I made to absorb the feel of the form before developing it...

Sketches can be any size

The design drawings for this chair were not much more than doodles really. Just go with whatever lets you work up ideas the fastest.

Here is another copy of the existing chair frame to get familiar with it. This much rougher one is a plan view.

Here is a first attempt at visualising how the chair back might support the sitter.

This is a sketch where I was exploring a bat-winged idea as the basis for chair back support.

Fusing original structure, seating needs and possible wing concept

This sketch shows how spending the time on familiarising with the original structure helps work up a possible extension of the concept, when combined with the more abstract wing idea.

Second design

I wasn't convinced by the wing design, so tried out another possible idea. This one is much closer to the end design.

And here is the same design attempt, but imagining the back. Note - when I drew this view, I realise that to get the arms to look good, I needed shoulders. This also helped me work out that the height of the back support needed to be higher.

As you can see, it is not so important to create masterpiece drawings. You just need to start to visualise what the end result might actually look like. It is better to sketch faster and looser, so you get more ideas without getting too invested in the quality of an individual drawing

It's not just about visual design

The drawing above was about the look and feel design of the chair, but I also needed to make drawings of the construction design. This is a drawing I made to try to work out how I would need to build up the chair back, in order to carve it into the intended design.

Physical prototyping

Drawing is a very powerful visualisation aide, but for furniture, sometimes you eventually have to build something physical to test if the visual design is actually comfortable to sit on. Here is an early attempt to see what the slope of the back and the angle of the arm-rest supports should be.

Note the square uprights are not fixed. I was holding them in place to try out various angles

This is an attempt to suss out how the claw ends would need to be positioned and thus how the arm-rests would be constructed.

Here is a later version. The upright base of the back is in place, but I was still working out exactly where the claw ends of the arm-rests should go. By this time, the claws were completed, so it was easier to work out the exact position needed.

Testing the seat back angle

Physical prototypes should be treated like sketches. They are there to quickly test ideas. They don't need to look pretty. Like sketches, it is safer to make them fast so you don't get tempted to finesse them. Make them just to test if ideas work successfully when translated into physical form.

Here, I used stuff lying about to mock up a back. This is a shelf, some polystyrene and a spare kitchen cupboard door and tape to hold it in place.

From the side

This is wide insulation tape. I bought a load reduced. It is good for binding as it is stretchy. It can be unwound too.

User testing

You need to try it yourself to see if the design actually is comfortable for the user.

I wanted to try different angles, so I used a piece of bendy steel to try out different vertical curves, to determine the final size of the back and the shape of its curve.

Here it is from the front.

Unexpected discoveries

Physical prototyping is there to enable user testing. It can also inspire new ideas.

In this case, I only had used the steel sheet as it was easy to bend to try out diffrent curved shapes that I expected to make in wood later

The unexpected side effect was that the springiness of the steel acted as suspension and was even more comfy. This led me to change the structural design to incorporate a sprung loaded back.

You don't get that sort of insight with paper drawings alone.

Step 3: Basic Frame Building Technique Using Mortice and Tenon Joints

Before you can carve it, you must build it...

One of the challenges of making this chair was that it had to be both structurally solid as a piece of furniture and achieve a figurative creature-like look.

To do this required making a distorted variation on a standard chair construction, but the joints needed to be set at irregular angles. Additionally, the wood used to make the frame pieces had to be hugely thicker than is usual when the frame was being built, to allow the crooked limbs to be carved from the legs and rails

It sounds complicated, but practically, it involved nothing much more than making making a fat chunky frame using thick beams of wood, using mortice and tenon joints.

Here is the chair again in its final (2016) and its original (1997) forms. These joints occur at shoulders or elbows, but the carving means these are not really obvious. It just looks like one form.

How the chair base is constructed

Here is the base all joined together...

How this fits together

Here's an attempt to explode the jointed base into its constituent components. Essentially, it is a five-legged structure with nine joints.

Things to clarify the picture:

- Joints 1-8 are traditional glued mortice and tenon joints. Joint 9 is held together by a steel bracket.

- The front "leg" is formed from the gargoyle's head spewing out either vomit or its own guts.

- This has two mortice sockets cut into it which are the female parts of joints 3 and 4

- Into the mortices of joints 3 and 4 are fitted the tenons of the two front rails. These are carved as ears, shoulders, upper arms and ribcage of the body.

- At the opposite of each of these rails, there is another tenon that connects into a mortice cut into the head of each of the next two front legs, which are the gargoyle's forearms. These are joints 1 and 6.

- Into the two front "shoulder" rails there are also mortices cut to take the tenons from the rear rails, which are the gargoyle's torso. These are joints 2 and 5.

- These rear rails, like the front rails, each have a tenon at the opposite end too, which fits into a mortice in each of the two back legs at joints 7 and 8.

- The last joint is not a standard woodworking joint. This is joint 9 and it is formed where the two back leg joints (7 and 8) are pulled together onto either side of the rear tailpiece. A metal closing plate is bolted into each back leg and the tail piece to lock the three pieces together.

Example of how a jointed section is created

The explanation above describes how the finished chair base parts fit together in the final structure after carving. But of course, the legs were originally jointed together as great big fat pieces before they were carved.

Here is how one of the new armchair support joints was added in, to show how this was done. You can see that it is quite chunky. It is not a subtle joint. It was quite a large tenon, because it needed to be strong.

Start by squaring off the curved elbow to fit a square post

This was marked out, then shaved off using a multi-tool saw blade.

Once squared off, a tenon was marked out

The bulk of the tenon was cut out with a router

The mortices were cleaned up with a standard chisel

Tenons were cut into the upright posts. Note how fat the post was before jointing in. This was because a sweeping twisting curvilinear shape was later to be carved from it. The cross sectional area of the final upright is probably only a fifth of this original post. Most of the post was carved away as waste.

The mortice shoulders are also angled, because the post was to be inserted so that it projected at a slight outward angle.

Here is post in my hand, showing the scale. This was a 4" x 4" section reclaimed oak fence post. It was chunky!

Here I am fitting the tenon. You can clearly see how large the upright is.

After initial fitting the arm-test obviously looked rather square. It is best to think of them as blank 3D canvases, ready to carve. The block resting on top is a raw oak block from which a claw hand would later be carved. These hands were fitted later with a more unusual jointing method, using screws and glue/filler. That is in a separate step.

This wrist joint took a while to judge where to place it. This was not possible to get right until the chair back had been constructed, so that it could be sat in and the hand position tested for comfort.

Step 4: Carving Claw-hands for the Arm-rests From Green Oak Logs

One of my favourite things about the gargoyle chair is the sinuous bone-like arm rests and their claw ends. They look enjoyably grotesque and they also feel really good. The twisty arms are super smooth and they curve down into the slightly evil looking claw hands

They may look evil, but they are actually really comfortable to rest the palm of the hand on. The arm and claw curve down continuously to make this work.

Here is the right hand arm-rest in all its glory This is before staining and polishing. You can see the lovely grain.

Oak logs as raw material

It is easy to forget that wood isn't just something brown you buy down the shops. You can actually pick up raw wood in the woods. Who knew? To be fair, not all wood can be carved green without cracking as it dries, but oak is quite tolerant.

The claw end of the arm rests were carved from green oak logs. They were felled about a year earlier than I reclaimed them. I'd had them in the shed where I was going to carve them for some months, so they were reasonably stable.

TIP: if carving green wood, leave it in the place it will be carved for as long as possible beforehand, so that it can stabilise to the atmospheric conditions. This makes it less likely to crack as you carve it. Ideally this should be several months, but a week or two is the bare minimum.

This is what the claw looked like before carving - literally a log. It was a length of branch that was abandoned in the woods after a large oak had been trimmed back after falling in a storm.

Here you can just see the grain

Note - oak logs are very heavy. If you are collecting from the woods, be prepared!

I carried this log about a mile using this modded rucksack. If I'd just carried it in my arms, I wouldn't have lasted two hundred yards.

Roughing out the basic hand shape

The first thing I did was cut the logs to length then spilt in half with an axe.

In this shot you can see a half log and a half-carved hand

Working to a design in the mind

Normally when carving, I will draw the final object shape that I am trying to create, to burn it in the mind. Unusually, in this case, I didn't bother sketching what I wanted the claws to look like.

This was really just because I've drawn so many hands that in this case, I could see in my mind what I wanted and just ad-libbed from my imagination. As I've got two hands myself, I also periodically tried out creepy hand gestures to keep the proportionate directions of fingers about right

Even though I had no physical sketch to refer to, I still needed to transfer the mental image into the wood to act as a guide for roughing out. Here you can see the rough finger blocks being cut out of a log section. It is best to do this with a hand saw. Power saws tend to cut too deep accidentally. With a hand saw, you are more in control.

The basic block was carved roughly square. Here it is in the vice. You can see the pencil marks. These are lines to show where the finger blocks are to be cut.

Before getting the chisels on it, I also made some stop cuts to help remove wast areas faster without splitting down the whole log.

TIP: Stop cuts will save you getting very annoyed. They are cuts made parallel to the grain to allow you to cut into concave shapes without the chisel taking off more wood that you want.

Wood will naturally split all the way along its grain. The point of stop cuts is to limit this. This allows you to remove bits like the black shaded area with the chisel later, WITHOUT accidentally cleaving off all the red area!

Time to get the chisels out

Amongst these beauties are my largest gouges. They can hack out great chunks of wood at a time while containing the damage with their curved profile.

You need the wood to be held firmly in the vice for this

Oak is hard and the ridges formed by the gouge grooves feel lovely.

As you progress, you will need to keep redrawing the shapes on as you cut away the waste wood they are drawn on. Here you can see where the rough shape of the claw emerging...

When roughing out the trick is not to be tempted try to start working on the fine detail until the rough blocking out is carved. Carving out these broad blocks is the 3D equivalent of sketching outlines in 2D.

Here is a claw after quite a bit of gouging.

From the side, it looked like this...

And after further carving, I could start carving out more of the detail of the claw-like fingers and their tendons running up the back of the hand...

It is important NOT to stand in one place. You need to move around the work you are carving, to make sure it looks right in 3D, not just from one angle. I have a heavy duty vice bolted to a board that means it is portable, so I got out in the lovely garden to do this.

By continuing like this, eventually the knuckles and claw details can be carved out

Here is the more or less complete hand. Note, it has not yet been sanded and fine smoothed.

Later on the hand was sanded at length using a range of attachments on the multi-tool.

The right claw hand, after sanding.

Step 5: Constructing and Carving the Arms and Shoulders

Sometimes you have to go freestyle...

Figuring out how to build up the arms and shoulders for the armrests was the most complicated and to some extent the most delicate challenge in the whole build.

Luckily, I wasn't too worried about exactly how it would end up looking. I just knew I wanted the arms to look strong but scrawny and sinuous - spindly rather than bulky.

And so, I just built the arm structure up by improvising as I went along and then ad-libbed carving them out. I had lots of fun hacking out the shape with tools like this reciprocating saw, before fine carving with a handheld power router.

Choose curved grain wood to suit the job

I wanted a nice curve round from the back to the upright supports for the claw hands. To make this work, I really needed some slightly curved lengths of oak. Conveniently I had this piece of log with a grain that naturally curved round an elbow shape, where the tree it was cut from had grown round a branch stump.

TIP: Using naturally curving-grained timber is a trick that medieval ship-builders used for strength. If you cut a curve from straight-grained timber it is inherently weak as timber is very strong along its grain, but not across its grain.

Think of it as the difference between trying to snap a log (very difficult) and trying to split a log (much easier).

Here is the log I used.

I very roughly sawed this length-ways into these weird shaped planks. The grain follows the shape of the wood and has a natural bend in it at the top end - perfect!

Here you can see the same two planks after they had been shaped a bit and attached crudely with screws onto another piece of wood on the back. The screws had to be deeply recessed, so that I didn't hit the metal of the screw later, when carving the wood.

I then built up the shape of the shoulder area was just by adding on more blocks of wood until I had enough to carve back from. Where possible, I glued them on without screws, also to avoid hitting screws when carving.

For pieces being glued on wthout screws, I scratched into the grain of the wood. This exposes the grain fibres for the glue to get a good hold of. This is much stronger than just gluing smooth wood.

This piece was largely a filler, so could be just glued on in this way as it was not needed for structural strength

Once the blocks were built up and the glue dried, I further secured the ends of the arms with horizontal screws into these blocks. They already had vertical screws into the back panel, so this was very strong. The visible saw cut in this piece was also filled later to strengthen it.

As well as the more obvious large blocks, I glued in filler blocks plug the gaps. These were not screwed as they would be used to carve figurative shoulder detail into. They didn't need to be screwed in as they were not structural either.

The arms joints needed to be rock solid. Securing them with screws at multiple angles locked them in place firmly.

Here are the shoulder joints with all the blocks in place, before carving back

Let the carving begin...

Adding these solid blocks is the 3D equivalent of sketching out major compositional shapes on paper when drawing. You block in the big shapes, then work on the detail to get the final shape.

And so, once the glue had dried on the blocked out shoulders, I could carve continuous contours from them down the arms using the reciprocating saw.

In close up...

You get the idea. This phase was roughing down towards the final composition. I was deliberately not trying to work on the fine detail at this stage until the shape was in place.

I also got to use my beloved draw knife. This is an amazingly subtle tool considering how simple it is. It can hack off off wood quickly if you need to. It can also shave off super thin slivers if needed. Because it has a broad flat blade it leaves a smooth tooled finish too.

Here is the chair's right arm, more or less structurally complete. It needed a lot of smoothing before it was finished, but the basic shape is there.

And here is the left arm of the chair at the same stage.

I used some other very good tools to get the shape to this stage including these fabulous hand rasps. These detail rasps are called rifflers.

Here's a pointed-end riffler

And here's a curved club-ended riffler...

These traditional pointed-teeth wood rasps cut through wood fast, but they do leave crude gouge marks which can be hard to get rid of, especially when they cut across the grain. These should only be used at the roughing out stage.

From rough-sawing to fine-routing

Only once the basic shape of the arms had been established, did I move onto the actual fine carving and finishing. This was with a handheld router.

Here it is. This is a Bosch POF52 router with the guide cradle taken off. It is a fairly lightweight model which is not amazingly powerful for hardcore plunge-cutting joinery, but with the cradle off it is perfect for hand carving. It's got a decent 500W motor, so it has plenty of power for this. These were also quite a successful model so there are lots of them about and they are really cheap to buy second hand.

Very conveniently, the end-barrel of the router body that normally fits into the cradle, is exactly the right size to fit a standard drill handle. You need this as you need to be able to control the router with a good grip.

The killer addition here though is the drill solid tungsten carbide rotary rasps. These babies are super hard and can even grind soft metals up to mild steel without taking the edge off them. They can easily cope with carving hard woods like oak.

Treat routers with respect...

Health and safety!

This router has a no-load speed of 27,000 rpm, so you should have control over it. For starters, NEVER attempt to use plunge cutter bits for this. They will kick back really dangerously. The rotary rasps here are quite fine toothed, so will cut away happily, but not catch.

Here you can see how to hold it with one hand on the added handle and the other on the router body, with the thumb over the switch to turn it off if you need to.

This is the business end of my favourite rotary rasp bit. Its dome end can create all sorts of curvey shapes and even deep recesses. It is a joy to use.

It is blackened because the friction can singe the wood if you press hard. This won't hurt the tungsten carbide. I've used these bits for more than twenty years and they haven't been blunted at all.

Using a rotary rasp

Carve against the direction of the cutter

TIP: When using a rotary rasp in a router you draw the cutter in the opposite direction to the spin. You will feel this is right when you do it. If you carve in the direction of spin, the blade rolls along the wood. You need to do this to feel it.

In this image, the rasp is rotating clockwise as you look down on it so that the teeth are also cutting in the clockwise direction. The cutter is being drawn from right to left to carve.

Carving with this tool is surprisingly expressive. You can carve out all sorts of shapes freehand using it.

Here it is in action

Step 6: Using Pin Joints and Glue/sawdust Filler to Put the Armrests in Place

This step has a bit of overlap with the last one which was about building up the basic wooden blocks from which the the arm-rests and their shoulder joints were carved.

This step is really a closer look at the specific joint I made to deal with attaching the claw ends onto the arms.

I had carved the hands separately from the arms before I even know exactly how the arm rests were all going to fit together. I could possibly have planned these joints a little more, but I wasn't quite sure how the arms would shape out until I started carving.

The joints described here are all constructed using a combination of screws and sawdust impregnanted glue. It is quite a crude method which is hardly one you would use for fine cabinet making, but it is effective and versatile, so its worth seeing how it was done.

Basics

Here is the chair's right hand wrist joint. This is where the claw hand meets the vertical arm rest upright support and the horizontal arm-rest. You can see it is little more than a three-way butt joint that is reinforced with 4" screws. There are several screws her at various angles for strength.

The basic weakness of this joint as it stands is that while the screw holds the pieces tightly together, they could have developed play round the screw pivits when the chair is in use. This would lead to them starting to come apart and not be rigid.

This one shows the top of the other wrist joint. Some screws have the heads set in deep recesses and some were deliberately shallow to allow some of the screw metal to show. The slightly Frankenstein look this gave added to the overall weirdness. Even so, I didn't want there to just be bare screw heads showing, so these were ground down later.

Two more views of the same joint.

TIP: With oak, you must drill pilot holes for screws or you will split the wood. Similarly, you must countersink the holes so the conical screw heads don't cause splitting either.

To fill the various gaps, spaces and holes, a strengthening filler was used. This, I made from PVA wood glue and oak sawdust from previous cutting of the logs and planks.

I got the sawdust from carving shavings, filtered through a garden sieve.

I then sucked them up in my shed vacuum cleaner them up and used the saw dust from the cylinder.

I ask you: Who hoovers their garden?

It was mashed together in small batches as needed, so that it didn't dry up too quickly to use.

And crammed into all the various gaps.

This is easiest with a flexible spreader. I made this one from a plastic bottle.

As well as filling holes, a small amount of additional shape was also added by moulding the paste. This is like modelling in pulp-based papier mache, but MUCH more crude.

In this joint, I also added some cross-strength with a wooden insert. While using the sawdust paste in the joint is a bit like sculpting in chipboard, these additional wooden strengthening fillers build strength by having layers of crossed grain, a bit like the strength of plywood.

Here you can see how crudely this is built up.

The wooden inserts were trimmed off once fully dry. This is a modellers tenon saw. It's quite useful as it bends and can get in curves to cut.

This technique looks very crude and it is, but once hard, the paste can be sanded back surprisingly effectively.

Here is a shot of the finished right arm after filing and sanding, but before staining and French polishing. The joint holes are visible, but look more like scars (possibly a little like stigmata holes)

After staining other dents and recesses were accentuated so the screws blended in more with the scorching and pitting elsewhere on the arms. This obviously works on a chair which is intended to have an aged and slightly distressed finish.

On the shoulder joints, I also extensively used variations on the sawdust paste method and insertion of wooden fillets.

Here is the basic crudely screwed -on end joint of one of the shoulders. The screw holes were later filled, the saw cut was fitted with a strengthening fillet, and additional blocks were added on top.

This is the same joint after smoothing (not quite at the same angle) showing an additional block (top right), some filled holes and a sanded down screw head.

Further reinforcement with wooden blocks

On one wrist, I felt it needed something more to keep it together, so I used a large wooden fillet to make use of the strength of the oak grain. This is effectively like adding a tenon into the joint after the event.

I had cut out the rectangular recess by plunge cutting using a saw blade on a multitool.

The block used was a tight fit and like the other fillets, was left with rough edges to bond into the glue better.

It oozed glue when tapped home.

Like all PVA glue leakages, it is easy to wipe off with a damp cloth as long as you do this while wet.

Once fully dry, the protruding wood was trimmed flushed before sanding.

After sanding it looked like this

This was OK, but was a little too obviously a rectangular block. To reduce this, I decided to dig it out a bit and add some filler to blend it in more to the distressed aged look.

The final finish.

Step 7: Using an Old Saw to Make the Spring-loaded Suspension in the Chair Back

As described in a previous step, during rapid prototyping of the chair back, I had discovered by chance, that the steel sheet I happened to use for a quick mock-up was really comfortable to lean on because of its springiness and flexibility.

However, while this stainless steel sheet was bendy, it wasn't elastic enough and didn't fully spring back into position each time it was leaned on. This meant it wasn't suitable on its own as it would sag backwards over time ruining the shape of the chair.

I realised I would need a counter spring to make sure it returned to position after the sitter got out of the chair each time. Conveniently, I had just the thing. This knackered old saw was blunt and no use for cutting. However, hand saws are made from springy steel that will snap back straight when bent and released.

(This is a classic example of the creative re-purposing technique of ignoring the names of objects and thinking about their properties. It wasn't a saw, it was sprung steel with wood screwed onto to it!)

I did a further quick prototype by just taping the saw onto the steel plate to test this.

It worked perfectly. Another satisfying example of left-field recycling.

Removing the steel blade was easy. The handle was held on by threaded bolts that were easy to undo.

It was that simple.

However the saw end was diagonally angled. It needed to be square.

I simply squared this off with the angle grinder.

To give this nice symmetrical spring!

The saw-blade spring was the right length, but needed to be positioned further up the back of the chair base.

I realised I could insert the saw blade into the plywood back of the chair base with a simple groove cut into the board. Once I had worked out the right position, I marked it with a pencil...

Then drilled down into the board at the right angle for the steel to lie at.

This was quite fiddly because of two fixing screws really close to where the slot hole was needed. I had to use the reciprocating saw a bit

And the Dremel with a high speed steel drill bit...

While the screws were in the way, they also turned out to be quite handy, because I realised I could use them as locating pins. I just needed to cut corresponding slots in the saw-blade. I marked these out using a Markie felt tip pen.

I cut the slots out with the angle grinder

And because sprung steel will only bend so far before it snaps, I could pop put the two pieces of metal with the long-nosed pliers.

The spring could then be simply slotted into place in the lower chair back. The two screws located it quite firmly.

A satisfyingly simple join.

Here is the spring in its final position

All that remained was to fit the steel sheet over the saw-blade spring mechanism.

Holding the sheet temporarily in place with tape, I marked out the final arched chair back profile shape.

I cut this out with the reciprocating saw, using a steel cutting blade.

In close-up you can just see how sharp the edges are after cutting.

I filed these edges smooth with a handheld metalworking file.

Then I drilled holes into the two pieces of steel and riveted them together with the pop rivet gun.

TIP: Saw blades are VERY hard. You will need a tungsten carbide tipped drill to get through them. A normal high speed steel drill will just blunten.

Here you can see one rivet in place and another about to be pulled.

In this back view of the spring mechanism, you can just see the four rivets.

Here it is a later on with the wooden back piece back in place. You can't really see it, but the lower end of the steel sheet is screwed to the wooden chair base.

This mechanism is pretty simple, but is really effective and made the chair much more comfortable.

Step 8: Building Up the Chair Back

To make the back of the chair, I needed a fairly large and slightly convexly curving piece of wood to carve. There was no way I was going to find a piece of decent oak of this size and shape, so I used planks to build up a basic stock shape, which I could get to work on.

This shot shows the back with the main spinal shape sketched out in 3D, prior to the detailed carving of vertebrae and their processes (processes are the sticky out bits you get on vertebrae). You can just about see the wooden layers used to create the underlying structure from which the back was carved.

The raw material for the back of the chair was these rather tasty oak planks. They were retrieved from a skip a long time before this project. I think they were off-cuts from fascia boards. A very good find anyway. Way too good to be thrown away in the rubbish.

The first thing to do was to size how big the back-piece needed to be to blend in with the rest of the back on the chair frame. This was easy enough. I just needed to initially fit a board to the spring mechanism shown below, that I had built onto the chair base as described in the previous step.

And here is the first layer of plank being measured and tested for fit. This piece would later be connected to the metal spring plate and the convex form built up on top of this.

The base piece of this back form needed to wrap around the spring plates. For this I recessed it with a joiner's router to a depth of about half an inch (12mm) or so.

Thus...

This would be hidden inside the chair back eventually, so it didn't need to be finished off especially carefully, as long as it was even.

To build up the rest of the form, I simple cut out more pieces from the same board material with the jigsaw. For the first two I used an angled cut to create a tapering form.

The whole form was made from these four pieces. The pencil marks were from where I had been drafting the layout.

The four pieces were glued together one by one into one form, starting with the top-most two smallest pieces.

Then the next...

And so on until the basic rough shape was created

This was left to dry for a few days, then was ready for carving. Here is the initial work on sketching out the basic vertebrae shapes. The crude pencil marks seen previously were used to guide the initial stop cuts.

The stop cuts allow you to carve into the wood without splitting right down the planks. The fine detail of carving the back is in the next step.

Further reading on 3D sculpting using wooden layers

TIP: Layering is quite a simple technique that can help you make almost any shape in wood. If you want to explore this further, I have a whole Instructable about how to extend this layering method to transfer a sculpted model in polystyrene to wood.

This is a useful way to prototype and design a shape in a soft material and then transfer to a hard material. It's a bit like a sort of super-crude 3-D printing!

INSTRUCTABLE: "Arduino controlled animatronic wooden head (reading lamp)"

Step 9: Carving the Skeletal Back of the Chair

The lovely grotesque curving beauty of the back rest is my favourite thing about the chair. I love how it looks and also how it feels. This was the most detailed part of the build.

Here's how it was done, but firstly, here is the beauty...

The spine may look like one extended piece, but it was formed from multiple blocks of oak as described in other steps. This was almost exclusively carved with the handheld router using rotary rasps.

If you only ever buy one carving rasp, get one that has this form. With care, you can carve almost any shape. Also, it's solid tungsten carbide so it will never blunt if you only use it on wood. This one is more than twenty years old and just as sharp as when I bought it.

All the carving on the back was done with this bit.

Here's the back in its raw state before any fine sanding or French polishing. The main challenge here was carving a consistent look across multiple pieces...

This was complicated as the chair back is articulated in the middle with a sprung loaded hinge for comfort.

Because the top half of the back is a separate block attached to the internal suspension springing, it could be removed and carved separately to start with. Later on, I attached it to the base to make sure it was consistent.

I like this shot. It shows the slight chaos involved.

Here is the main chair back at the beginning of the carving. You can still see the weathered face of the boards it was made from.

At the top, you can see the large pencil lines drawn to sketch out the spacing of the vertebral processes to be carved. The lines are where grooves will be carved. In the foreground, you can see that these pencil lines have stop cuts in them to start off the basic shape.

Here is another close-up. You can just see the circular pencil guides which indicate where the spiny vertebral processes will go.

The stop cuts were pretty rough hacks

The back after lots of carving into the stop cuts.

This is the saw I used for the stop cuts. It is a small circular hobby saw. It originally had a safety guard which I removed to make it easier to use.

Here is the fabulous hand-held router that did all the carving work.

It is worth using ear defenders and eye protection (and essential when using the saw). These are swimming goggles. They are really good.

I also use standard reading glasses with the router. These are not so protective, but router-carving doesn't really throw out much debris. I got enough protection and could look at the detail using the magnification.

The router makes gouge-like grooves. Here are some cut across multiple planks.

Here is the mini saw again. It can cut really quite subtly, although it's best for concave cuts.

Close up of mini saw cuts.

Of course, if you take the guard off you need to make sure you have a very good hold on the saw. The sawing action is like gently stroking. Go too deep and you get kick backs.

For the really detailed bits, I used the Dremel extension drive. Here it is with a fine rotary rasp.

Though you can also use standard hardened high speed drills. These are very good for detail, but are quite brittle and can snap. Definitely use proper safety eye wear if you use these!

Here are shots of the spinal detail being worked up with the various tools described.

This is quite early on, so is deliberately crude initially.

More saw cuts.

Router-cut grooves

Roughing out in the recesses between vertebral processes

This is not that difficult, but took a long time and requires patience.

From above.

At this point, the back was sufficiently carved to start integrating with the rest of the back in the base of the chair

Here is the lower back of the chair. This started with the original tail to which planks had been added. In this shot, you can see the wood being carved out into extended vertebrae.

This started with some grooves "sketched" into the plank.

This shot shows the back that was carved previously has now been attached.

Here you can see how the lower half of the back was carved across the various blocks of oak attached to the chair base.

The left side is largely still crude blocks of wood that have been built up round the original tail. You can see the holding screws. The right side has been carved out.

When you do this, you don't need to worry about the various colours of the various blocks that you start with. These oranges and greys are all surface colours. Here you can see the underlying consistent light greyish brown colour of the wood emerging as the very different blocks are carved out.

The form will emerge as you go. You can still just about see the edges of the underlying structural blocks here, but they are already very less obviously visible as the carving proceeds.

Here's a close up of the hinge. The foam padding is just visible in the centre. The blackish spots on the wood are where the rasp blackens the wood due to friction burns. These got sanded off later...

...using things like these barrel sander attachments on the Dremel (left) and the handheld router (right).

Here you can see the rough saw cuts I did to rough out the basic shape so that the base and the separate top part of the back matched up and the form flowed across both to make one long spinal column.

This is a close up of the shoulders at the hinge joint. The router used for carving and the mini circular saw used for hacking out waste wood are visible on the floor, here.

The same area looking at the right hand side.

Here it has come together

The various blocks have slightly different colours. These were evened out later using staining to age it later.

The back took days of carving...

...but it was so worth it. It looks magnificent!

Step 10: Sanding and Smoothing the Completed Chair

Sanding the carved wood smooth was a pretty epic piece of work on this chair. It took days. This was really fiddly because of the many protruding shapes and recesses. Happily though most of the fine carving was done with super-fast rotating cutters on the router and Dremel and these cutters leave a pretty smooth finish. The remaining smoothing was not hard work. It just took a long time to do across all the complex parts.

Oak before and after finishing

Just to show that a coarse log can shine when taken through progressive sanding, here's a side by side picture. Both logs came from fellings from the same tree so were exactly the same age and conditionss when collected.

Raw oak log

It did need planing a bit too before sanding

Super shiny finish on oak after finishing

Oak does take a fantastic polish...

Close up.

Main sanding techniques and tools used

All of these tools were used for sanding. All of them take different bits, sanding attachments or varying belt grades of sanding sheet or belt

- Dremel with extension lead (rotary cutters and carborundum grindstones)

- hand held router (tungsten carbide cutters and cylindrical sanders)

- mains and cordless multi-tools (triangular and finger sander attachments with various grits)

- filing sander (8mm sanding belts of various grits)

- cordless drills (cutters and carborundum stones)

I did use these "normal" sanders a bit too, but only on the fairly even convex parts of the arms and legs.

As described earlier, the power carving tools themselves do a lot of the work so sanding was not too difficult, it just meant really going over the chair methodically to take out all the little bumps and rough patches.

Hand sanding

Sometimes you need to feel it with your fingers...

And the final super finishing was always done with fine steel wool. This polishes the wood to an incredibly smooth finish. This really did make a huge contribution. If you've never used this, you must try it. It is remarkable.

TIP: Steel wool wears down fast. When you need a new bit, you can cut it with scissors. This is much easier than trying to rip a wad off.

Sanding in practice

Here, I am smoothing out some bumps on the gargoyle's scrotum with a pointed dome carborundum stone with the Dremel using an extension drive (there's a sentence you don't hear every day...)

The main tool I used for sanding was the finger sanding attachment on the multi-tool. It has a pretty fine point that can get into most recesses and it takes velcro sandpaper so I could use sanding paper pads from a fairly coarse 80 grit down through 120 grit to 160 grit and finally the 240 grit.

Here, I'm fine sanding the aforementioned scrotum to a nice shiny finish. Although these parts are not really obviously visible when the chair is upright, I wanted all the exposed wood to feel super smooth to the touch if someone did happen to come across them. The chair is intended to be tactile.

Feeling the way...

To make sure the sanding really did leave everything really smooth, I used my fingers and hands to feel it was enjoyable to the touch. I literally felt my way round the whole chair, area by area. This added to the time it took, but it was very important to do. I wanted it to feel so good that people would really enjoy running their hands over it. It was worth it, as it does feel lovely.

Here is the forearm after a fair amount of carving into shape. The dents and grooves are largely leftovers from the previous roughing out with saws and hand rasps. Even though I had carved most of these out by repeated passes with the fine router cutter, you can still see a few light ridges.

Here am feeling along the arm to see where there these ridges and any rough patches or lumps were to see which felt worst and needed a bit more carving out. At this stage, I was only making quite shallow final adjustments that didn't really change the form of the body parts noticeably, but they did change how the chair felt quite considerably.

To before starting the really fine sanding, I used a barrel sander bit in the handheld router to even out the ridges. These sanding cylinders are better for evening out than the hard tungsten carbide cutters. They don't tend to create ridges so the tactile experience is smoother. The only slight pain is that the cylindrical sanding sleeves wear down quite quickly, so it can get a bit tedious changing them (unlike carbide cutters which never wear down).

For these outer shapes I could also use a standard orbital sander. This a dirt cheap basic model, which is great for sanding convex shapes like this. The broad plate evens things out nicely.

The cumulative effect of these progressively finer grade abrasive tools is this lovely smooth raw grain. It is still not finished, but is quite close to the final finish. The beautiful grain of the oak is becoming much more obvious here.

And as already mentioned, it was important when progressively making it smoother, to keep feeling the work as I went along.

As the sanding grits got progressively finer, it started to feel really smooth.

In this case, almost all of the sanding was done with the multi-tool using a finger sander attachment.

Eventually the various different blocks that I started with became blended into one smooth form. This takes a long time and requires patience, but oak is a very rewarding material. Its warm hard smoothness feels really sensuous if you take the trouble to work it down stage by stage to a super smooth finish.

From rough to smooth

To show just how much change the sanding makes, here is the same chair as it was arm before the whole sanding process.

Sanding the very complex knobbly back

The detailed vertebral design of the back was always going to be tricky to sand.

I used the filing sander on this to get into some of the deeper recesses. (this is such a great tool!)

I also used the cylindrical sanders in the hand held router and the Dremel. Having two machines means you can swap between grits without hassle.

As when using the router with the carbide cutters, it is worth holding it firmly.

As described above, I continued to use my fingers to feel the smoothness of the various protrusions, bumps, recesses and other shapes as I went along. Even though it is bumpy, I still wanted it to feel smooth and continuous for anyone who brushed their hand across the shapes.

The cylindrical sander really worked for this.

The black singe marks were from the carbide router. The sander here took some of this off, but I left some on deliberately for ageing too.

I made sure to feel right into the recesses.

As well as testing for the smoothness of just gliding a hand over the ridges.

Sand paper recap

I won't go into detail about how to sand-finish in detail. The essential process of sanding and finishing is always about progressive passes of slowly finer and finer abrasives. Here are the various grades of paper I used. In these pictures, most of the sheets are for the rectangular profile orbital sander, but the same ranges of grades are available for the multi-tool velcro pads and the filing sander belts.

- 60 grit (really rough)

- 120 grit (medium)

- 240 grit (fine)

- 400 grit (very fine)

- Steel wool (for final finishing)

Rough stuff

I typically used 60 or 80 grit - for blunten off edges and bumps. Take care with this as it tends to leave quite deep scratches which are more hassle than they are worth.

Rough enough stuff

I didn't often use really coarse grade paper. This 100-120 grit paper is better as it leaves fewer deep marks. If using a power sander, you can use finer papers and let the power of the sander do the work.

Fine grade

240 grit will leave wood pretty smooth.

Really fine

And 400 grit even more so. For really fine sanding, use a well worn piece of sandpaper. It will polish the wood.

Definitely use steel wool

Steel wool is the business for final finishing. It smooths wood better than any paper and it can get into any corner as it is flexible. I used fine grade steel wool. I also used this on the intermediate coats of French Polish, to smooth off any tiny lumps where dust gets caught in the polish.

What a beautiful material oak is...

Step 11: Leather Upholstery in the Chair Back

The leather upholstery on this chair was quite a tricky piece of work. The main challenges were:

- making sure the leather upholstery blended into with the organic design of the carved wood

- making sure it was really comfy

- working out exactly how to fit it to such an irregularly constructed chair, especially the flexible back

The main back of the chair is based loosely on the belly of a crocodile. It was not so much intended to look like one as vaguely imply a slightly leathery reptilian feel. The seat itself has a central seam to indent it slightly in the middle for comfort. I also used some padded bumpers round the edges to provide more support and also to accentuate the organic feel.

Here is the finished chair. Very throne-like and very comfortable.

As a reminder, here is the original earlier version of the chair I built in 1997. It had no arms nor any real back support and while it looked more like a single animal, it was not really more than a stool and as a result, was not very comfortable to sit in.

This step is about doing the upholstery for the back of the chair. There is a separate step for the chair seat.

Chaotic upholstery

First of all, it is worth noting that doing upholstery is quite chaotic and involves lots of fiddly stuff with various tools and materials. It is best if you have as much space as possible. This picture gives a flavour of how this ends up in practice. Good fun though.

Using woolen carpet as a padding material

The first thing I did was to create a template for the upholstery shape. I happened to have some off-cuts of looped wool carpet lying about in the shed. I had saved these in case they came in handy one day. Carpet is quite stiff, but still flexible, so this turned out to be perfect.

I roughed out the basic shape I was going to need to create for the padding then taped it onto the chair to mark it out more accurately. The orange stuff is insulation tape. It is great for this.

The same piece seen from the back.

I marked it out to follow the edges of the chair frame using a Markie pen

Then trimmed it back. Here I am using my penknife, but I also used a Stanley knife on it.

Eventually I had an accurate cutting template for the chair padding.

As well as indicating the outline of the shape required, I could use the template to sketch out the rough look of the paneling I wanted to create to give the crocodile belly look.

At this point, I could start working with the lovely leather I had reclaimed from the discarded sofa.

Reclaimed leather does not come as predictable pieces. I had to lay it out to see the shapes I had available.

Originally I thought I might be able to create the panelling from one piece, with seams sown into it. I played about with the pieces to see if it was feasible, but I couldn't really get a big enough piece.

I decided instead to cut individual panels from the leather. This was a more efficient way of using the various scraps of leather I had to play with.

Making the panel templates from cardboard

I used strong cardboard to make a cutting template for the panels. I did this by creating a carved section that was one half of the shape I needed...

I drew round it onto another bigger piece of cardboard, then flipped it and drew round it again to make sure it was symmetrical.

I then cut out the full width template.

The basic shape was a more even curve than the original sketches I had made. This was because sewing it together would be much more even and consistent than a wavy line.

I then marked out a load of pieces...

I drew them close together to get as many panels as I could from the leather.

Leather is tough, but it cuts quite easily with dressmakers scissors which have a faint serration to grip the material.

Eventually I had a load of panels.

Before sewing them together, I drew a central line on them. This was a guide to help me keep them aligned evenly when sewing together on the sewing machine.

Then I just had to carefully sew them together. Obviously, these were stitched on the reverse side!

Eventually I had a single panelled piece.

Here is the finished panel as seen from the face side.

You can see the difference between the even curve of the stitched panelling compared to the original sketched concept on the carpet template.

I realised that I could use the carpet template as a backing for the leather, to help keep it in shape, but also to create a sleeve for mounting it onto the steel spring of the chair back.

And so, I attached the leather to the carpet, using hot glue. This worked well, because both leather and carpet are quite fibrous and the glue sticks into the fibres firmly.

I was careful to check that there would be room for the padding I needed to add later. If I had joined them flat, I couldn't have stuffed them nice and plump.

This had to be done quite methodically to keep it even.

One method of making the joints strong was to hammer the leather onto the glue. This forces the glue deep into the fibres and also forms an even more distinct edge shape to the leather.

You can see it is closely bonded

The sleeve that was formed was intended to slip over the steel spring mechanism in the chair back.

To allow the carpet panel to be threaded behind the lower part of the spring, I cut into the carpet to create loose, strap-like bands. The carpet couldn't just be slipped right over the steel plate because of various fixing screws holding the plate onto the carved wooden back.

Here I am trying out the sleeve on the spring and pushing polyester fluffy stuffing inside to plump up the padding. To tamp it in, I'm using a piece of plastic rod, but any flexible rod would do. It's best to use a smooth one or the fluff catches on it.

And here you can see the sleeve slipped over the top of the spring and padded in the top end, but still empty and loose at the lower half. The loose carpet flaps can be see just above the rear arm joints.

These flaps needed to be pulled very tight to fix the leather/carpet sleeve in place. This needed a way to pull them into place really tightly. To do this, I added tensioning wires that could be pulled into the tight space behind the plate. To attach the wires, I punched fixing holes in the carpet straps that I had cut earlier.

I tied strong multi-stranded wire onto this. This was galvanised fencing wire I had collected from a skip. The green thing is a threading needle that is actually half of a broken fibreglass archery bow. It was handy for this as it was rigid and long enough to thread the wire with, and soft enough to drill a thread hole into. Fibreglass has flex in it too, so could curve a bit when required.

Using the fibreglass "needle", I threaded the wire tensioning strap round the back of the steel spring plate of the chair back.

And did the same on the other side.

This angle shows why the straps are needed. The wires go behind the plate and then was pulled really taut, to pull the leather snugly against the plate. You can see one wire, not yet tensioned, to the left of the steel.

I continued pulling the leather into place using the wires in this way, working down towards the the lower half.

Towards the bottom of the chair back, as well continuing to attach the panel, two side bumpers were added, for comfort and to create a bit more of a snuggly shape. These bumper were made by sewing leather tubes from wide strips of leather.

These tubes were stuffed with wadding. I'm using some plastic trim here as you need something quite firm for this.

The bumpers were stuffed quite plumply.

This is the bottom end of the panelled chair back. You can see the bumpers on either side. These were tacked in first before the panelled sleeve was pulled into it's final position overlapping them.

You can see the ends of the tensioning wire were secured finally to a heavy screw that I drove into the base of the chair. The wire was pulled tight and knotted to the screw head. The left hand wire is tightened here. The others are not yet.

There were several sets of flaps used to wire-tension the leather. As I worked down the chair, I added more fluffy polyester wadding to plump the leather padding fully down the back.

Here I am threading a securing wire from the bottom-most set of fastening flaps. It is being threaded in front of the padded bumpers, but behind the steel plate. This pulled the base of the leather back padding firmly against the bumpers.

I had run out of the galvanised fence wire off-cuts, so I improvised using two pieces of gardeners green plastic coated training wire. This was quite good for this as the wire is thin and strong. It could be wound round the screw head tightly.

Adding the extra bumper at top of the back

Finally, as well as the bumpers to the side of the lumbar support area of the chair back, I also added another thinner bumper at the top of the chair back.

This was just another folded and stuffed leather strip, but thinner.

The seam was used to secure it behind the carpet backing of the panelled seat back. I used hot glue to fix it.

I glued in short runs and wedged in each section tightly using screwdrivers while the glue was still hot.

To complete the seat back, I added more plumping with fluffy polyester padding. You can see the inner bag of polyester that I had reclaimed from the abandoned sofa on the left. It wasn't just the leather that was useful.

Here is the chair back upholstery fully secured and with its padding fully plumped.

After the back was upholstered, I did the chair seat. This is described in the next step.

Foot note - health and safety

I discovered it is quite easy to sustain minor injuries while doing upholstery!

Scratches

Here's a cut from the stiff end strands of the fence wire springing back and catching my arm. This is one of those ones that I don't notice until I find blood dripping on something!

Burns

TIP: Be especially careful with hot glue guns. It is really rare to use a hot glue gun without getting some of the napalm-like scalding plastic stuck on your fingers. This will burn a blister in your skin in seconds. You always know if you get hot glue on you - it REALLY hurts - beware!

Cuts

The edges of steel plates can cut you pretty easily too!

Step 12: Leather Upholstery in the Chair Seat

This step shows how the main padding was fitted into the seat itself and how the leather upholstery was completed to blend in with the already upholstered seat back.

This is the chair after the panelled padded leather back had been completed as described in the last step.

Creating a cardboard template for the seat base support

To provide a really comfortable seat base I used a base of expanded foam with fluffy polyester filling material over the top of it to provide shape and extra softness. I had decided to build these two layers upon an underlying plywood base board.

The first challenge then, was to fit a base board into the irregular, vaguely pentagonal central space of the chair base. To do this, I created a template by using offcuts of cardboard. Rather than trying to trim one piece, I trimmed corner pieces for each of the various corners, then just taped them together. You can see these pieces here.

I used the template to mark out the shape on a piece of quarter inch plywood. Here it is after I had cut it out. At this stage it was just resting in place for measuring up.

To fit the foam I already had a template. This is the lower end of the carpet template I had cut out in the previous step about upholstering the chair back. The top half of this carpet template had been cut off to form part of the internal reinforcement and structure of the chair back.

This is the lower piece which had been cut off, which was all ready to use as a marking template.

Here it is laid on a piece of expanded foam. This foam was another material reclaimed from the discarded sofa.

After cutting out a foam piece using the template as a guide, I then trimmed a slight diagonal edge all around the foam piece. This was to soften the edge of the seat, so it was more comfortable.

Here is it being tested for fit. During this fitting process, I discovered that it was much more comfortable to have a gap in the middle of the chair. Here it is being held in place using tape to stop it sliding about.

As well as being more comfy, the shape of the seat pad felt more aesthetically in keeping with the chair back and the chair in general. It has a slight unsettlingly sensual feel that I quite liked.

Building the seat upside down

The layers of the seat pad construction were built up in reverse order with the chair upside down on the workbench. This picture always makes me smile.

Firstly the leather was tacked into place. This is the first test fitting of the leather using a plain piece of leather. However, I found that the twin-mounded shape of the underlying foam was lost when using a plain piece, so I took it out and tailored it to follow the contours of the foam better and keep the two buttock-supports visibly distinct.

To do this, I stitched pleats into the leather. This ridge on the underside of the leather seat-pad cover created a groove on the outside when padded.

Once the newly re-tailored leather seat cover was tacked back in, the next layer to be added was a generous amount of fluffy polyester filling. This stuff is like a sort of open, springy cotton wool, but with lots of bounce. If you squash it and let go, it just expands back out again. It will do this indefinitely and does not settle or flatten like other fillers (like feathers).

You can see that I used a lot of it, despite this layer only being maybe two inches thick when compressed later.

This was stuffed tightly into the cavity against the leather cover

And then the foam piece cut out earlier was fitted on top of this. The foam is wider than the gap in between the wooden frame and when pushed in, expanded slightly on the other side, which gave a nice snug fit.

This shot is just before pushing home the last edge of the foam onto the fluffy polyester.

Finally, the board cut out earlier was forced down onto the foam and held in place. I used screws for this because they are reversible and I needed to be able to remove the board later to check if the padding was the right amount so I could adjust it. I also needed access to fit the final padded bumper round the edge of the seat later.

I could now see the chair almost as it would be when finished. You can just see the creased groove in the leather seat cover, created by the pleats sewn in earlier.

From another angle

Adding the final edge bumpers round the seat pad.

Before I could fix the seat base in place permanently and complete the trim, I needed to add the final edge bumper that would sit at the front of the seat. This was another strip of leather sewn into a tube in the same way as in the step about making the seat back.

Stuffed in the same way with fluffy polyester filling.

By tamping it in bit-by-bit.

This one was slightly different though as I sewed fixing straps along it's length.

These needed to be fairly strong and evenly spaced. They were used to pull the bumper tightly into place against the seat pad.

The bumper was first positioned against the seat pad. The pad looks flat here because the stuffing has been removed to allow the straps to be pulled under the leather cover and tacked onto the wood underneath it.

With the chair upside down again, the fixing straps were threaded through. Here you can see the pleat in the seat cover too.

The straps were then fixed onto the inside of the wooden frame rails with carpet tacks.

Then the polyester filing and foam was re-fitted back into the seat pad.

And then the supporting plywood base plate was screwed back in place.

When fitting the board, the foam gets squashed. As a result the board is held firmly in place against the retaining screws by the pressure of the board pressing back against them.

These screws don't look good though. Once they were in place, a plain leather cover was fitted over the base board which looked much better. It also feels good. Although it is unlikely anyone would put their hand under the chair, if they did, I wanted it to feel just as good underneath as it does on the main visible parts of the chair.

This leather cover was tacked in place as tightly as possible

You can see the finished effect better from this perspective.

The upholstery completed