Introduction: Beginning to MIG Weld

From our Welcome to Welding lesson, and our Tools and Materials lesson, we went over how the welder works, and some of the principles of welding any metal. In this lesson, we begin to practice welding on thin sheets of mild steel.

Your welder will come with proprietary instructions on how it should be set up in your work space, follow it's manual closely. I've learned that each electric welder is a bit different brand to brand, and model to model. I know it sounds like a drag, but time with your tool's manual will make you the best possible operator. Once you have set up your MIG welder, you are ready to begin practicing laying a bead, and observe how the welder fuses metal.

To follow along with this lesson you will need:

- MIG welder, loaded with .030". wire

- 2x small sheets 16 ga. cold rolled steel

- Soapstone

Step 1: How Does MIG Welding Work?

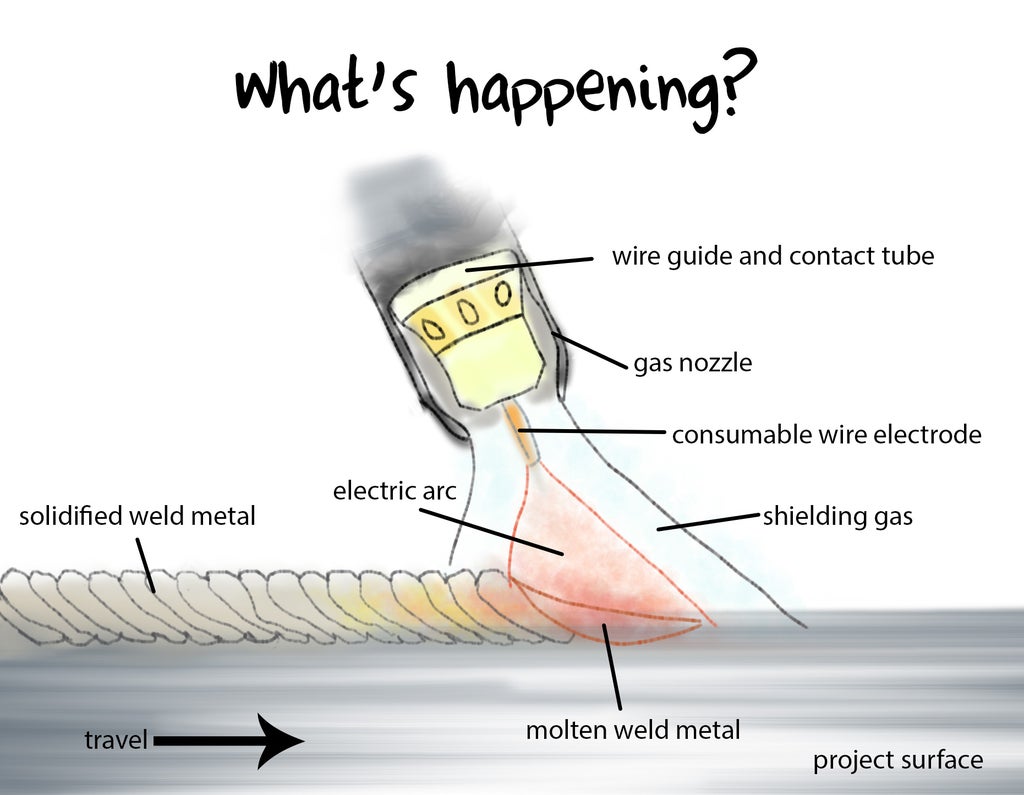

MIG welding uses a power source and an electric wire feeder that feeds a wire electrode through a welding gun, also referred to as a torch. This wire feed pushes the consumable welding wire with a set of drive wheels and a constant speed motor to turn the drive wheels. When you squeeze the trigger on the torch, you start the flow of electricity from the welder to your grounded workpiece, and the continuously charged wire electrode is burned up in your molten weld pool, often referred to as the puddle.

The wire electrode comes in various coil sizes, or spools depending on the welds to be performed. These spools can be mild steel, stainless steel or aluminum in accordance with the materials you are welding, and can contain hundreds and even thousands of feet/meters of wire. Most welding machines have various functions allowing timed feeds and variable speeds.

The wire is housed in a cable that also contains a shielding gas hose. This allows the electrode to run smoothly without bending or kinking. The shielding gas, an inert gas made up of argon and carbon dioxide, protects the weld from contamination during the welding process. If oxygen gets into our weld, it causes immediate rust, making the weld brittle. Shielding gasses are used to create a protective bubble around the arc and molten metal while the welding is being done.

A gasless wire is available for mild steel. This is called flux-core welding. This process is useful in outdoor, or on-site situations where a gas tank is impractical to lug around, or breezes are a concern by blowing away any protective shielding gasses.

Step 2: Understanding the Welder

The Welder

On the outside of the welder, you will find two knobs. One knob controls the speed of the consumable wire electrode that comes out of the torch, and the other knob controls the amount of current that the wire electrode carries. Usually, an increased voltage requires an increased wire speed. This is because you are sending more heat into the wire, and it is being consumed at a faster rate.

Inside the welder, you will find the spool of wire and a series of rollers that pushes the wire out to the welding gun. There isn't much going on inside this part of the welder, so it's worth it to take just a minute and familiarize yourself with the different parts. Each manufacturer of welders designs this mechanism a little differently, so be sure to refer to your welder's manual if you are confused about these components.

The large spool of wire will be held on with a tension nut. The nut should be tight enough to keep the spool from unraveling, but not so tight that the rollers can't pull the wire from the spool. My old shop teacher used to call it 'monkey-tight, not gorilla tight'.

If you follow the wire from the spool you can see that it goes into a set of rollers that pull the wire off of the big roll. This welder is set up to weld steel, so it has steel wire loaded into it.

The Gas Tank & Regulator Valve

Assuming you are using a shielding gas with your MIG welder (as opposed to a flux cored wire electrode), there will be a tank of gas behind the MIG. The tank is either 100% Argon or a mixture of CO2 and Argon. This gas shields the weld as it forms. Without the gas, your welds will look brown, porous, and splattered. Open the main valve of the tank and make sure that there is some gas in the tank. Once the wire passes through the rollers it is sent down a set of hoses which lead to the welding gun. The hose of your welder contains the charged electrode and the shielding gas.

The Welding Gun

The gun consists of a trigger that will initialize the wire feed, gas flow, and the arc of electricity. The wire is guided by a replaceable copper tip that is made for each specific welder. Tips vary in size to fit whatever diameter wire you happen to be welding with. Most likely, this part of the welder will already be set up for you unless you have unboxed a brand new welder. The outside of the tip of the gun is covered by a ceramic or metal cup which protects the electrode and directs the flow of gas out the tip of the gun. You can see the small piece of wire sticking out of the tip of the welding gun is the consumable wire being pushed through the gun from the welder.

The Ground Clamp

The ground clamp is the cathode (-) in the circuit and completes the circuit between the welder, the welding gun and the project. It should either be clipped directly to the piece of metal being welding or onto a metal welding table. The clip must be making good contact with the piece being welded for it to work so be sure to grind off any rust or paint that may be preventing it from making a connection with your work.

The above image shows the positively charged anode making contact with the spool of consumable wire fed to the torch, and the ground clamp is permanently anchored to our shop's worktable.

Step 3: Your MIG Welding Studio

MIG welding with gas is not intended to be performed outside. Wind from working outside is capable of disrupting the flow of shielding gas from our welding torch to our base material, contaminating it with oxygen. If your weld has oxygen in it, it will rust instantly, and your weld can crumble like a cracker. Welding indoors may need some specific electrical considerations. A 220 outlet does not look the same as the common 110 outlet, so if you buy a beefy welder for your home, you may need to have an electrician come wire a special outlet for your home.

In the perfect world, you’d be doing all of your welding on a workbench and you wouldn’t need to move your welder around to accommodate the pieces and projects you are working on, but realistically, you will be moving your welder constantly. Getting a rolling cart that holds your welder, gas cylinder, and welding supplies you commonly use is a great way to minimize the heavy lifting associated with dragging a welder around your shop. This welding cart instructable by Seamster is a great beginners welders project that will make moving your welder a stroll in the park.

A welding table or metal workbench is essential to any welding shop. Getting your work off the ground ensures improved ergonomics while working on your project, and less awkward maneuvering. Check out this worktable by jmpratt. It is equipped with outlets for easy grinding and cutting without ever having to remove your project pieces from its grounded table top.

Step 4: What Materials Can Be MIG Welded?

MIG welding can be used to weld steel, stainless steel, and aluminum. Each metal will require slightly different gasses, welding wires, and current settings. Furthermore, different thicknesses of material may require larger welders. The heavier and thicker the metal being welded the more powerful welding machine needs to be.

For home MIG welders, a machine rated between 140 and 220 amps is most likely the best choice. This would allow working on metal thicknesses from 1/16″ up to 1/4″ including pipes, tubes, flat bar, round bar, angle iron, sheet metals and square hollow sections. (We go over recommended welders in the Tools and Materials Lesson)

Step 5: Commonly Used Hand Tools

There are some essential tools that every welder will need to produce clean welds then properly finish their projects. When welding I always try and keep the following within arms-reach: an angle grinder, some welding pliers, a mild steel brush, and a hammer.

An angle grinder contains a high RPM motor-driven spindle onto which a cutting wheel or some other task-specific implement is attached. Grinding metal is part of every step of welding, from prep to finish. By changing the discs on the grinder, you can perform a huge range of tasks. Before welding, we will cut metal to size with an angle grinder, and then grind down material to be sure we are performing a weld on the cleanest possible surface. After welding, you use a grinder to clean the weld joint, smooth tall welds, and find holes within our weld joints.

Each angle grinder brand may be a bit different but are principally the same in their components. Each angle grinder contains a guard, handle, and spindle onto which a grinding wheel is attached. The guard can be positioned to multiple directions, with an arrow on it indicating which way it will throw ground-down material. The handle can be attached to either side of the grinder so that you can get maneuver the grinder into tight spaces when necessary. Having two hands on the grinder is advised; because they spin so rapidly, they can skip and jump if not properly secured.

When selecting a grinder, look for a grinder with a broad paddle switch instead of a conventional toggle switch. This ensures that the tool turns off as soon as you release it from your hands.

Grinding wheels are commonly affixed to the spindle in two ways. Some wheels will be threaded and will just screw onto the spindle, other grinding wheels will need to be secured with a locknut. A special lock nut for your spindle will come with the angle grinder when you purchase it, as well as a special tool for turning the locknut.

You have lots of options for what kind of wheel you attach to your angle grinder. Most commonly you will be using flap wheels and cut-off wheels. Flap wheels are rated similarly to sand paper, with specific grit sized being called out on the back of the wheel. The lower the number, the faster it will rip down material. Cut-off wheels are used for making cuts in rod and pipe, but also handy for tough grinds that would cause excessive wear on a flap wheel.

Wheels with wire brush bristles on them are used for removing paint and potential surface contaminants from steel. There are even grinding wheels available for polishing. Your local hardware store will have a whole section devoted to angle grinder attachments in its power-tool section, just be sure you are getting the wheels that are suited for use with metal, as some are just designed for use with plastics and wood.

ALWAYS wear PPE when you are using a grinder. They are extremely dangerous tools if used improperly, so be sure you always have safety glasses on when using, at the minimum. Ideally, you are using safety glasses under a grinding visor, with ear plugs, and a respirator to make sure you aren't breathing in any metal particulate.

Welding Pliers will be needed time and time again to dislodge your electrode from your gun when it becomes jammed, gently bending thin pieces into shape, and most importantly cutting excessively long bits of wire between weld beads. If your electrode is sticking out too far from the gun, it creates a poor ground connection to your working material, and thus a poor weld.

Welding pliers are awesome because the distance of the snipping blade from the opposite edge is exactly 3/8". The same distance your electrode needs to be poking out from the torch. This means you can hold your pliers flush to your torch's gas cup when trimming the electrode and perfectly cut down the wire before you perform your next weld.

A wire steel brush is clutch to keeping your material's surface clean between welds. The welding process can cause a very thin layer of scorched material to build up on your project's surface. You can thwart potentially contaminated welds by scraping off this layer with a wire brush. Be sure that the bristles of your brush are the same material as your base material. Using a stainless steel brush on a mild steel project can also cause contaminations in your weld.

Hammers and dollies can be essential when setting up a work piece for welding, but also during the course of your welding process. These tools help you straighten and “fine tune” a joint before you weld, as well as knock pieces back into place between welds. I find that the thinner the metal pieces are, the more frequently I have to bang them back into place.

Step 6: Setting Up the Welder Before Welding

Assemble the torch:

- Thread the contact tip over the wire and screw it into the torch finger tight.

- Attach the gas cup. Some welders have a slip-on cup, while others will be threaded. If your gas cup is a slip-on cup, move the cup so that the contact tip is flush with or recessed about 1/8” within the cup.

- Clamp the ground for the welder to your work or the metal workbench. Like clean metal, a good ground connection to shiny metal makes welding easy and results in high-quality welds.

- Plug in the welder, make sure the torch button isn’t depressed and turn ON the welder using the large switch on the front of the machine.

- Turn the voltage and wire feed speed to the minimum setting.

Stand to the side of the tank opposite the regulator and open the valve on the gas cylinder. This is just another safety precaution, just in case the regulators fitting has become loose, you don't want to be blasted with gas. I usually don't crank the valve all the way open, for the sole reason if I need to shut it quickly, I can do so with one half-turn or so of the knob.This might not seem like such a big deal with Argon or CO2, but when you're working with flammable gasses like oxygen or acetylene you can see why it might come in handy in the event of an emergency.

Check your gas flow. While the torch is positioned well away from any grounded surfaces, pull the trigger to initiate the flow of gas. Check the gas flow on your regulator. Use the adjusting screw to set the working pressure to between 15 and 20 CFH (cubic foot hour). The gauge is most accurate while gas is flowing. Snip away excess welding wire and discard whatever wire was fed through the gun during this check. The wire should stick out of the gas cup 1/4” to 3/8”, or the distance of your pliers from the gas cup.

Set heat and feed rate. Open the panel of your welder to find the settings reference for your material. The voltage and wire speed knobs should be set to the type of metal your project is, thickness of that material, and the diameter of the wire spooled inside the gun.

Before operating the welder, double-check your safety gear. Make sure that your:

- Gloves are on.

- All skin is covered by leather or natural fibers.

- Your welding hood is turned on and in front of your face. Start with the welding hood lens at shade 10 and adjust as needed. If you are working in a cramped space, consider a fume extractor.

- Protect the people around you. Set up welding shields to block harmful rays and blinding light from those passing by.

- Check the condition of the welder – controls, torch, work lamp, gas cylinder, gas lines, and cords – for any damage such as cracks, burns, chips, or dents.

Step 7: Clean and Prepare Your Metals for Welding

Cleaned bare metal makes for the best welds. Dirt, paint, rust, etc., make welding difficult, create more fumes, and weakens weld joints.

It pays to prepare the area thoroughly by removing potential contaminants with an angle grinder, wire brush, denatured alcohol and/or acetone.

If you are practicing welding on hot rolled steel, be sure to grind off the mill scale before you attempt to weld on it. To make sure your steel is free of debris after grinding, wipe it with a solvent like alcohol or acetone on a disposable shop towel.

If you are practicing your welds on cold rolled steel, you only have to wipe off the oily film from the mill. Acetone works best to remove oil but is much more of an intense solvent than denatured alcohol. If you choose to work with acetone, it's imperative that you wear nitrile gloves, or any gloves rated for handling chemicals while working with that solvent.

Wire brushes and wire grinding wheels are labeled for use with steel, stainless or aluminum. If using a wire brush, make sure that it matches the kind of metal you’re welding so you don’t pollute your welds (or the brushes). I mark the outside of the brush with a permanent marker so I never risk cross-contamination.

Step 8: Pulling the Trigger

There are four things we control as welders when we are wielding the torch: Distance, Angle, Speed, and Heat. I was taught the acronym D.A.S.H.

Distance

Angle

Speed

Heat

In your welding practice, you will find that these four things are constantly in balance to create a perfect weld joint. If your material is burning out, consider moving faster, or turning down your voltage and feed settings. If your welds appear to have a lot of bubbles or deformities, check the distance and angle of your torch.

There are two welding motions you will always come back to: tacking, and running beads. The basic process of laying a bead is not too difficult. You are trying to make a small loop with the tip of the welder, or itty-bitty concentric circles moving your way from the top of the weld downward. You can also hear when you are getting a good weld, the noise the welder makes will barely fluctuate. The motion of welding is a little bit tricky to get the hang of but once you get the hand-eye coordination down, it becomes second nature. I think within 30 minutes of practicing laying beads, one could be ready to take on a larger welding project.

Position the torch perpendicular to your work 1/4” to 1/2” above, then tilt the torch 5 to 15 degrees along the path of travel so it will be pointing back towards the weld. This is called pulling the weld. If you were to push the weld, you would tilt the gun towards the direction you are welding. You get slightly better penetration by pulling welds. Pulling a weld bead isn't always suited for your project, as it creates more heat in the weld pool, so if you need to cause minimal heat distortion, it is best to push your weld.

Pull the trigger to start the weld. Look for a molten pool to form and then begin moving the torch slowly away from the pool. The pool should follow the torch. The video above was shot through a welder's hood, although it is still hard for the camera's sensor to pick up on the details of the molten weld puddle. The puddle is the active area of your weld. This molten pool is where the gun directs a beam of electricity by feeding a constantly melting wire electrode into your base material.

Inspect the weld after you are finished. It will be very hot, so pick it up with pliers or thick leather gloves, or leave it on the table until it’s cooled. It's best to hold your hand away from your material to sense if it is still radiating heat.

A great weld will have a small amount of metal rising above the base metal, parallel edges that blend smoothly with the base metal, and fine, smooth ripples across the surface. I've heard seasoned welders say it should resemble a 'stack of dimes'. It may take some time to create perfect welds, so be patient and take any opportunity to practice.

Step 9: Practice!

If it's your first time welding you might want to practice just running a bead before actually welding two pieces of metal together. You can do this by taking a piece of scrap metal and making a weld in a straight line on its surface.

Begin by practicing tacking. The gesture is so small, imagine that you are literally writing a small cursive E with the tip of the burning electrode. Next, practice laying beads about an inch or two long. If you make any one weld too long your work piece will heat up in that area and could become warped or compromised, so it's best to do a little welding in one spot, move to another, and then come back to finish up what's left in between.

Understanding the Heat Affected Zone (HAZ)

When any material, but particularly steel, undergoes a thermal cutting or welding process, the material -make-up of the workpiece changes. This heat-affected zone refers to the area of steel on your base material that has undergone a structural modification because of heat. When we ignite the welder on our base material, molten metal flows towards the torch, slumping around the weld. This means that your material around your weld is actually slightly thinner than the rest of your base material, and your weld is thicker than your base material. (This also means that your weld is stronger than your base material) This can make metalworking a bit unpredictable. The HAZ is most noticible by the rainbow of color that emerges around the welded area.

Do this a couple of times before you start actually welding so that you can get a feel for the process and figure out what wire speed and power settings you will want to use.

Every welder is different so you will have to figure these settings out yourself. Too little power and you will have a splattered weld that won't penetrate through your workpiece. Too much power and you might melt right through the metal entirely.

What are the right settings?

If you are experiencing holes in your workpiece than your power is turned up too high and you are melting through your welds.

If your welds are forming in spurts your wire speed or power settings are too low. The gun is feeding a bunch of wire out of the tip, it's then making contact, and then melting and splattering without forming a proper weld.

You'll know when you have settings right because your welds will start looking nice and smooth. You can also tell a fair amount about the quality of the weld by the way it sounds. You want to hear continuous sparking, almost like a bumble bee on steroids.

Step 10: Class Project

Practice laying a bead on some cold-rolled sheet steel. Cold-roll is great because it needs minimal prep, just a wipe with acetone or alcohol. Hot-rolled steel has a mill finish that needs to be grinded away before it can be welded. In my opinion, anything that cuts down grind time is the way to go.

Begin by prepping your sheet metal by cleaning it. Once the piece is clean, use a piece of soapstone to mark the letters you want to write out. The soapstone wipes off easily and is not visible once you have welded over it.

I suggest beginning by making tacks where your letters form corners. In my case, for the C and the O, I placed tacks in the midway points of the curves. You may have letters without curves, smart! As you begin to tack, notice where (if at all) the steel begins to distort and warp from the heat.

Begin to literally connect your dots. Writing out letters gives you great practice for 'seeing' your weld pool, as well as beginning to develop hand-eye coordination. You can flip your piece over to see if you are getting good penetration. As you work, observe how the metal begins to warp and twist. Your base material is heating, expanding and then cooling and contracting so rapidly that it will begin to take on a twisted shape.

Can't wait to see what you write on your sheet steel! Share your project in the class assignment space below.

Step 11: Clean-up!

It is good to get into the habbit of a cleanup ritual in any shop, but especially shared workspaces. (I recommend watching Tom Sach's Working to Code for anyone who loves making.) To ensure the best and cleanest space for yourself the next time you want to work in your studio, or the next shop user, follow the steps below.

- Turn the wire speed and voltage to minimum.

- Close the gas cylinder valve (turn clockwise).

- Pull the trigger until both gas gauges read zero to purge the lines.

- Unscrew the regulator screw a few turns until there is no resistance.

- Turn OFF the welder.

- Put away all tools and safety gear.

- Move the screens back to their original position.

- Brush off your work table, sweep the floor.

It's wise to stick around your workspace for at least 30 minutes after your last weld or grind, just in case any flying slag or spark began to smolder on burnable material around your shop.