Introduction: Pallet Butchers Block Style Worktop

In The Beginning....

For reasons of cost saving, my other half and I were looking

at ways of DIYing a worktop for the bedroom to go on top of her drawers to make a dressing table. After binning a couple of ideas we can up with the idea of a butchers block style worktop made from the chunky cross-beam sections of pallets that often get ignored or thrown away.

But before I started work on a 200cm x 70cm worktop, I decided to have a whirl at a bit of a proof of concept, and offered to do a mini-version for a pair of steel drawers that doubled as a bedside table, figuring it was better to mess this up than mess up the full size version. So – on with the instructions.

Materials

This was all done with pallets, which – as we all know – are almost always pine, and often low quality pine. As a result it was never going to be suitable to use for food preparation as pine’s just too soft to handle chopping and such. If you’re wanting to have a food preparation surface then go with oak or some other hardwood. However seeing as this will just be a benchtop with no more than a night-time snack on it it’ll do just fine

I used the cross beam sections of pallets that are typically about 36mm x 75mm, though size varies depending on the pallet,. The main thing is to aim to get lengths of timber that will create a worktop at least 30mm thick (vertically) and with an equal width.

Step 1: Step 1 – De-nailing, Cutting & Setting Out

The first order of the day is to take the lengths of timber and pull out every nail from the timber, as I wanted to rip down the timber to 35mm x 35mm lengths (essentially cutting the timber in half). Speaks for itself but given I’d be ripping the timber down on a table saw it’s essential to get rid of any metal from the timber: if a nail snaps off or won’t come out then it doesn’t get ripped down.

From there the lengths of timber were ripped down to 34mm (depth) by 36mm (width) lengths, and then it’s time for a bit of chop-saw action.

I decided to take the “random” approach to how long each individual length of timber should be, so cut them to anything from 75mm to 200mm in length – it really didn’t matter as it could all be mixed and matched come assembly time

Finally I set out (roughly) the individual bits of wood into a pattern – I know the final board had to be a minimum of 600mm wide and 450mm deep, so as long as each “laid out” length exceeded that I could trim it back down with a circular saw later

Step 2: Step 2 – Gluing & Clamping

Once I had the thing set out as I wanted it, with the wood nicely mixed up to form an irregular layout, I got on with the gluing and clamping. Each section of wood was given a good coat of strong wood glue, and the block was laid out in layers from front to back with the “sunny side” facing upwards (remember to put a bit of newspaper underneath as some glue will inevitably squeeze out at the bottom and you don’t want to glue the block to your worksurface). Once I got to over 45cm worth of depth I clamped the whole block as tightly as I could get it from front to back, then hammered in the timber from side to side in order to close up as many gaps between the blocks from left to right. Don’t worry if there are any gaps between the blocks as there’s a few tricks you can do to fill those gaps later.

Once clamped up I left it for 24 hours for the glue to set solid

Step 3: Step 3 – Cutting & Sanding / Smoothing the Block

This is dusty, noisy, and time-consuming, but it’s essential; so suck it up...

First thing I did once the clamps came off was to take the circular saw out and cut off the excess wood to make a block 600mm x 450mm. At this point the surface of the block was quite uneven with some height differences between neighbouring blocks. If you’ve got a planer/thicknesser then just wang the whole block through that to even it off. If – like me - you’ve not got any fancy tools like that then it’s time to bring out the belt sander and get busy: Start with a good rough grade of sandpaper to take off the excess wood, and then gradually work down to finer grades of sandpaper. Once it was fairly smooth, I shifted down a gear to an orbital sander and a very fine grade of sandpaper to smooth the timber off.

From there it was just a case of whip out the router to put a nice edge on the block edges, and a final hand sanding with some very fine sandpaper, and it was all ready to finish & stain

Step 4: Gap Filling & Staining

If – like me – you haven’t got a perfect fit between all the bits of wood and there’s a few gaps that need filling then fear not: there’s help at hand. Get down to the nearest supplier and buy some Wood Filling Wax – this is a soft wax coloured in a variety of wood shades from pine through to mahogany via light and dark oak. Because it’s wax you can shave off slices and force them into any gaps and trim it off to give a relatively seamless finish. It won’t look perfect, but – like grout does on a tiled wall – serves to cover all sorts of DIY botches. I used a Stanley knife blade to help trowel in the wax and then scrape off any excess, though people with more sense may prefer to use a spatula or something safer.

Once the wax is in any gaps, it’s time to oil and stain it. The colour stain (if any) is down to personal taste – I decided to go with what was termed “Jacobean dark oak”, and over the course of a few coats of stain darkened the wood nicely. From there it was just a case of adding a couple of coast of finishing oil and it’s job done

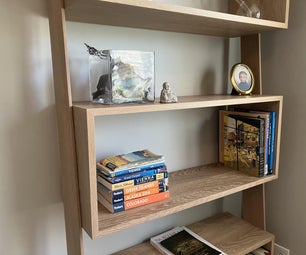

Step 5: Step 5 - Fitting and Done

The easiest part – in this case the worktop was going onto a set of metal cabinets, so it was a simple case of take the drawers out of the cabinet, drill a few holes in the cabinet top, and then screw up into the worktop – nothing more fancy than that.

Step 6: Final Thoughts

So that’s my first Instructable. Looking back I’d have done a few things differently: I’d have invested in a couple more sash clamps as they really allow you to ratchet up the compression which would have saved on a small amount of gap filling – so I’ll be off to buy a couple of extra clamps before I try the full-sized version; and I’d have spent a little longer sanding as the woodstain did highlight a few areas where my sanding was less than perfect. But apart from that I’m happy with it, and hopefully it shows that any fool with a few tools can build a decent looking worktop